A few years back, in the week before Pesah, I was somewhat surprised to see an ad on my Facebook scroll for a Passover seder at a nearby Italian restaurant. This was not a kosher restaurant, and clearly all the more so during Pesah. So OK, there are Jews in this world for whom kashrut, for Pesah or otherwise, is not so high on the list of priorities. But the thing that got me was the line, “A Very Reformed Seder Service (20 min.).”

Now, leaving aside the term “reformed,” which many Reform Jews read as a slur – reform is an ongoing process, not something that was done in the past – the enticement that the ad seemed to be presenting was that this seder experience would be long on food and short on ritual, discussion, or singing.

Now, it’s curious that Facebook thought I would be interested in this seder (perhaps the algorithm has since improved). But all the more so, it’s curious that some people would be so inclined as to minimize the best part of Pesah, that is, the story, and (I presume) toss out many of the essential, traditional food items in favor of a pasta dinner? Particularly because, being the second-most-observed ritual of the Jewish year, the seder formula clearly works.

Prior to this year, statistics have shown that about three-quarters of American Jews come to a seder. What will happen this year is probably a dramatic decline in the number of seder attendees, because my assumption is that the majority of us go to somebody else’s seder, and in our current circumstances, we cannot do that. (That is the primary reason, BTW, that I am live-streaming the second-night seder from my home.)

But what makes the seder so popular? Is it the food? Is it the story? The songs? The gathering of family? The short answer is, yes to all.

This will not be the first time that I have mentioned Marshall Sklare, the Brandeis sociologist who chronicled American Jewry in the middle of the 20th century, suggested that American Jews are most likely to maintain Jewish rituals that:

- May be redefined in modern terms

- Do not demand social isolation (i.e. requirements that separate the Jew from the wider society; yes, I know that sounds curious in the present moment!)

- Offers a Jewish alternative to a non-Jewish holiday (e.g. Easter, Christmas; this was something that was brought to my attention by one of our teens at a USY “Lunch & Learn” I facilitated last week, so it’s still valid)

- Centers on the child

- Is infrequent (e.g. annual, rather than weekly or daily)

Sklare pointed to the Pesah seder and the lighting of Hanukkah candles as being the best examples of such rituals in his book, America’s Jews, published in 1971. And really, little has changed in the last four decades: Pesah may still resonate because it pushes all those buttons. And Dr. Sklare’s thinking seems to still be on the money, half a century later. In this time of decreasing Jewish engagement, particularly outside of Orthodoxy, Pesah is a model that still works.

Away from the cold, academic glare, however, something else is true: Pesah works because we make it work. Perhaps in accord with Sklare’s first observation, that a ritual is likely to be observed if it may be redefined to suit contemporary issues, the message of Pesah continues to resonate with us. Slavery is still an unfortunate reality of today’s world (go to slaveryfootprint.org for more information on that); poverty and oppression may be found just about wherever we look. Those members of our people who fought for civil rights in the 1960s read the haggadah in that context, and there are those who read it today with the various ongoing struggles for equality – for women, for gays and lesbians, for non-Orthodox Jewish movements in Israel – in mind.

But I think there is more to the story.

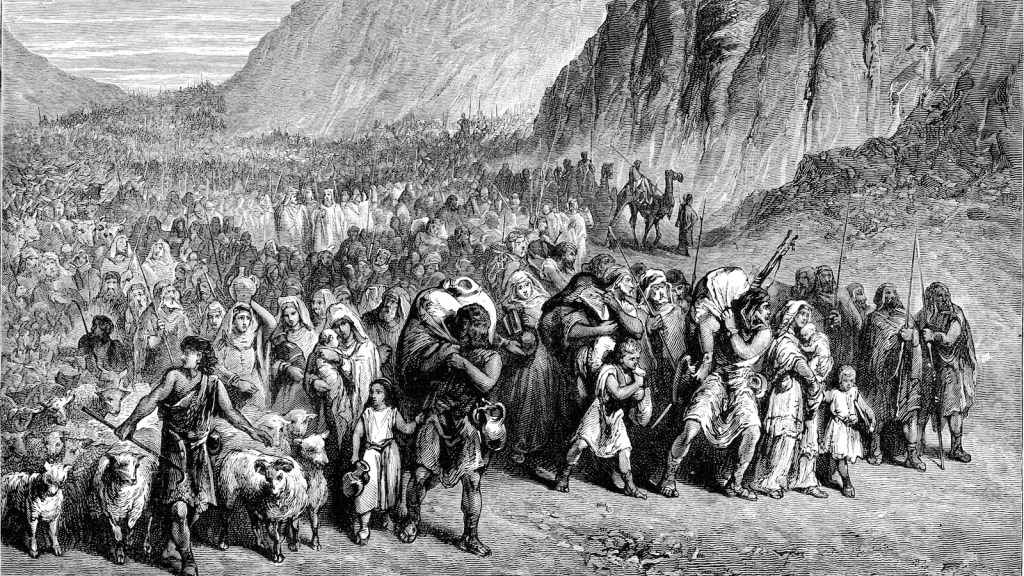

In the central portion of the seder, the telling of the story of the Exodus from Egypt (the item identified as Maggid, “telling”), there is a classical midrashic exposition of a passage from the Torah. The passage is the one that begins, “Arami oved avi,” “My father was a wandering Aramean.” (Deut. 26:5-8). You are probably familiar with it. The Torah presents these verses as the proto-liturgical monologue that the Israelites would recite when bringing their first fruits to the kohen, the priest, on Shavuot, and it encapsulates the story of Jacob and his family going down into Egypt, where they became a great nation, and then were enslaved, and God took us out of Egypt with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, etc., etc.

Within the midrash is the following comment on four words from Deut. 26:5:

וַיְהִי שָׁם לְגוֹי גָּדוֹל. מְלַמֵּד שֶׁהָיוּ יִשְׂרָאֵל מְצֻיָּנִין שָׁם

Vayhi sham legoi gadol. Melamed shehayu Yisrael metzuyanim sham.

They became a great nation. It teaches that the Israelites were distinguished there [in Egypt].

The Rabbinical Assembly’s “Feast of Freedom” haggadah (which I use in my home) elaborates on this as follows:

[The Israelites] became unique… through their observance of mitzvot. They were never suspected of unchastity or slander; they did not change their names and they did not change their language.

What makes us a great nation, ladies and gentlemen, is just as true today: we have our own heritage, our own traditions, our own laws. We also have our own language, the Hebrew language, which underwent a tremendously successful revival in the last century as a modern tongue. We also continue to keep our own Hebrew names, which we continue to use, for example, when we call our daughters to the Torah for bat mitzvah, and when our sons stand under the huppah, and at various other points in the Jewish life cycle.

This is our Jewish framework. But in addition to this, wherever we have lived, we have also taken on some of the aspects of the wider (i.e. non-Jewish) society, although for the most part we were never entirely assimilated to the point where we lost our tradition. Indeed, you might make the case that it is in fact Judaism’s flexibility that has enabled us to maintain our distinctiveness while living among non-Jews, to be both Jewish and something else.

Rashi, living in 11th-century France, spoke French and followed some French customs (he was a wine merchant, and historians suggest that he also wore a beret, smoked Gauloises, and exuded ennui).

Maimonides, in 12th-century Egypt, was a court physician to the sultan in Cairo, who treated Jews and non-Jews.

Moses Mendelssohn, widely considered the first modern Jew, joined the elite salons of 18th-century Berlin while continuing to practice his faith.

Theodore Herzl, in the late 19th century, was a secular Hungarian Jewish journalist, and yet he arguably launched the most successful modern ideological product of Judaism, that is, Zionism.

Throughout our history, although we kept Hebrew and our names and the Torah, we have navigated the wider culture and adapted to new environments and new host societies. And we have incorporated some things from the non-Jews around us as well: foods, including ritual foods, vary tremendously within our communities. And music and spoken languages and a whole range of minhagim, of customs, differ greatly depending on where your ancestors landed.

Yet there are certain commonalities of Jewish life that have continued for two thousand years or more – just one example: leather tefillin were found at Qumran, the site where the Essene sect lived at the northern end of the Dead Sea 2,000 years ago. But in every generation, each of us has seen ourselves come forth from slavery to freedom in our own context. We have never lived in a vacuum; we have continually scoured our tradition for contemporary relevance, searching for how the great works of the Jewish bookshelf continue to speak to us. Etz hayyim hi lemahazikim ba. The Torah is our Tree of Life, and in holding on to it we have upheld our nationhood even as we have clothed it in new styles and fabrics.

Had we been rigidly committed to one particular mode of living, Judaism could have died many times over: when the Babylonians destroyed the First Temple in 586 BCE. Or when the Romans laid waste to the Second Temple in 70 CE. Or after the great yeshivot around Baghdad closed up shop in the 11th century CE. Or after the Expulsion from Spain in 1492. Or after the Shoah / Holocaust.

So here is a suggestion. When you sit down to your seder on Wednesday evening, do what Jews have always done: make it yours! Make it relevant! Don’t just do what you’ve always done. That is NOT how Jews do it!

Here are some examples:

When the Four Questions come up, don’t just limit yourself to those traditional four. Ask more questions!

When telling the story of Pesah, don’t simply read what’s in the good ol’ Maxwell House haggadah. Have somebody summarize it in their own words. Get up from the table and act it out! Assign parts! Have everybody improvise parts of the story! If you have time, prepare some costume items: a staff for Moses, a crown for Pharaoh, a megaphone for God (maybe there is an app for that?), etc.

Have discussion questions prepared: What are you a slave to? What are the things that you are grateful for? What are the things that make your life bitter? In what ways do you feel free? Why is spring the best time of year? What hametz-laden item do you miss the most during these eight days and why?

These ideas work for families, for children, for sullen teens, for adults, everybody!

Ladies and gentlemen, what makes Pesah work is you! Your creativity, your enthusiasm, your joy. It’s not just about the kids, as Sklare suggested. It’s about you, living here in 21st-century America.

So go ahead, set the text of the haggadah to the music of Lil Nas X, or to the music of Hamilton, or whatever. Make it yours. Make it relevant. That is how we will maintain our Jewishness and the eternal appeal of our rituals. Hag sameah!

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Delivered at Congregation Beth Shalom, Pittsburgh, PA, Shabbat morning, 4/4/2020.)