I think I know where Bob Dylan is.

I’m sure that you have all heard that Mr. Dylan, aka Robert Zimmerman, joined the most elite club in the world this year: he won the Nobel Prize for Literature. And it seemed for some time that he was avoiding the honor. The Nobel committee had a hard time finding him. He did not return phone calls. It seemed that he was not interested in claiming the prize. (Perhaps, unlike many Nobel laureates, Dylan doesn’t really need the money or the kavod / honor.)

Although he eventually agreed to accept the prize, Mr. Dylan seemingly snubbed the Nobel institution by skipping the award ceremony, citing “pre-existing commitments.” A New York Times reporter tried to discover what, exactly, Mr. Dylan’s commitments were; he was not performing that night anywhere in the world, and he did not seem to be at any of his various residences (at least the ones that the reporter was able to check).

I suppose this is not too surprising for a performer who has always seemed to alternately loathe and love his audience. He may be best known for angering fans at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 by pulling out an electric guitar, a deliberate affront to the folk scene of the time. His performances have been unfortunately erratic; you never know when you see Dylan which Dylan you’re going to get.

Regardless, looking back over his 50+ years of music, there is no question that (a) he deserved this award, and (b) his lyrics are essentially timeless. They are as incisive today as they were a half-century ago.

So it seems that the Jews have yet another Nobel laureate among our ranks (some count our tribe’s prizes at an impressive 20%, although that requires casting a wide net of the ever-contentious definition of “Who is a Jew?” I’m sure Mrs. Zimmerman is very proud, wherever she is.

But I think I know where Bob Dylan is. He’s in mourning. He’s deeply, deeply embarrassed. He’s nursing his wounds. Actually, our wounds.

When I heard Patti Smith singing “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” for the Nobel award ceremony, it hit me. I think I know why Bob didn’t show up. Bob was not there not because he had another engagement but because his heart is broken. I think that Bob simply cannot handle today’s reality.

Never mind that the CIA believes that Russia hacked our election. Forget that a climate-change skeptic has been nominated to head the EPA, an oil executive with ties to Russia to head the State Department, and to head the Department of Energy a man who once said that if he were president, he would eliminate the Department of Energy. Never mind the chief strategist who used to run the premier website dedicated to peddling racism, sexism, anti-Semitism and conspiracy theories.

Leave all that aside for a moment, if you can. The biggest casualty of the current moment is the truth. What has come to the fore in 2016 is that many of us (with, by the way, diverse political views) have been deceived by fake news stories and distracted by social-media’s unquenchable desire for ever more clicks on ever-more-sensational items. When we become committed to false narratives and outright lies that are retweeted by authority figures, when folks in dire straights are so desperate that they are willing to swallow campaign promises that are so obviously far-fetched, I am very concerned for the future of our society. Truth has been compromised, and trust is being eroded.

As a non-political example, try to change the mind of somebody who has accepted the idea that vaccination against measles is dangerous. Although the concerns regarding autism have been debunked, and it is abundantly clear that the benefits of vaccination outweigh any perceived risks, it’s a lie – a fake news story that simply will not go away.

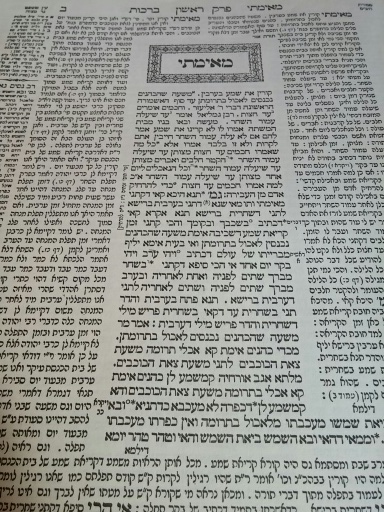

In rabbinic literature, the truth is understandably very important – so important, in fact, that there are multiple passages in our textual tradition about witnesses, people called on to testify to the truth. Witnesses in Jewish law have a whole host of restrictions and expectations. Rabbi Hanina (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 55a) tells us that the Hebrew word for truth, emet, is the personal seal of God. We come to kedushah / holiness through truth.

The founding fathers forged this nation on the basis of a handful of simple truths. How will we know the truth, when there is so much falsehood? How will our rights remain unalienable, if those truths are no longer self-evident?

Oh, what did you see, my blue-eyed son?

Oh, what did you see, my darling young one?

I saw a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it

I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it

I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’

I saw a room full of men with their hammers a-bleedin’

I saw a white ladder all covered with water

I saw ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken

I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children

And it’s a hard, and it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard

And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

Bob’s blue-eyed son has traveled the world, observing the depth and breadth of Creation and humanity. His innocence is long gone. His youthful idealism has long since been trampled by the truth. And in the song, the son is a witness to truths that must be told.

I learned from Rabbi Wikipedia that Bob’s Hebrew name is Shabtai Zisl ben Avraham (Wikipedia neglected to mention his mother’s Hebrew name; if he ever shows up here and Milt gives him an aliyah, I guess we’ll find out.)

Bob wrestled with his Judaism for many years. He even toyed with Christianity, but he came back to us.

And meanwhile, this is the week of Yisrael. We who wrestle with God. And the character that assigns this new name to Ya’aqov is the angel with whom he wrestles in Parashat Vayishlah.

The commentators go different ways on who, exactly, the angel is. Rashi cites a midrash (BT Menahot 42a) suggesting that this is his brother Esav’s ministering angel. I have always preferred the beautiful notion, echoed by the Gerrer Rebbe (aka the Sefat Emet, the “lip of truth”), that Ya’aqov is actually struggling with himself.

But rather than focusing on the angel, I’d rather consider the struggle. This is not wrestling, I think. Rather, they are dancing — locked against each other all night long, neither willing to forfeit the lead.

We are all engaged in some kind of holy dance — with ourselves, with our community, with our work, with our leaders, with our family, and so forth.

This delicate dance — the waltz of ages, you might call it — is an attempt to move forward with our lives even as we acknowledge and try to manage some of the brokenness around us. We cling to our mystical partner for dear life, hoping that the ground does not give way, that we don’t trip or stumble. Just like Ya’aqov and the mysterious heavenly visitor. We dance with the truth.

Oh, what’ll you do now, my blue-eyed son?

Oh, what’ll you do now, my darling young one?

I’m a-goin’ back out ’fore the rain starts a-fallin’

I’ll walk to the depths of the deepest black forest

Where the people are many and their hands are all empty

Where the pellets of poison are flooding their waters

Where the home in the valley meets the damp dirty prison

Where the executioner’s face is always well hidden

Where hunger is ugly, where souls are forgotten

Where black is the color, where none is the number

And I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it

And reflect it from the mountain so all souls can see it

Then I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’

But I’ll know my song well before I start singin’

And it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard

It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

Dylan ends with a hopeful note: those of us who are committed to the truth can help repair the world.

The hard rain has begun. It will be up to us to continue to dance through the rain, to take on the struggles that come, to stand up for the many people whose hands are all empty, to illuminate the face of the hidden executioner, to safeguard our waters, to make sure that souls are not forgotten.

Wherever we are headed as a society, I hope that our people will always be able to stand for the truth, even when it hurts. Truth matters more than partisanship. It matters more than victory. Truth outweighs budgets and process and matters of diplomacy. It is the essential check in the system of checks and balances.

As we approach Hanukkah, the holiday wherein we recall our duty to spread light in an otherwise dark world, the optimistic take-away may be that our tradition continues to mandate the pursuit of light and truth: that we as a people will always be compelled to lift up the downtrodden, clothe the naked, take in the homeless, and feed the hungry.

Shabtai Zisl ben Avraham, if you’re listening, please know that hiding from the truth is not what we Jews have ever done. In fact, we stand up for the truth, for the facts on the ground, for what is right for humanity. And we need you now as much as we did in 1962 when you first told us about that hard rain.

Return to us, all of us here on the dance floor as we continue this waltz of ages.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Congregation Beth Shalom, Shabbat morning, 12/17/2016.)