As I get older, I find myself more willing to accept a complicated truth about human life: you are never finished. No long-term project, no personal mission, no ideal to be implemented is ever really complete. We are all works-in-progress, and all of our human endeavors are forever in progress.

This is, I think, an essential piece of the human condition. Life is not a middle-school algebra problem, where there is always a simple answer awaiting the one who takes all the correct steps. Life is definitely not a series of 3-4-5 triangles. It is far more messy. We start new tasks or relationships with zeal and abandon them mid-stream. We change course. We fail at being the parent we hoped to be, or the spouse we thought we were, or the exemplary child we aspired to be.

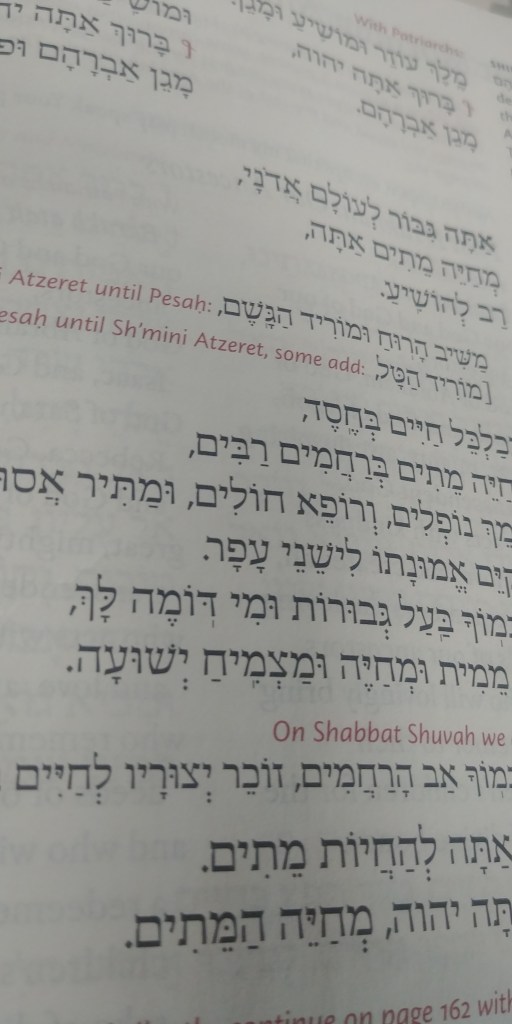

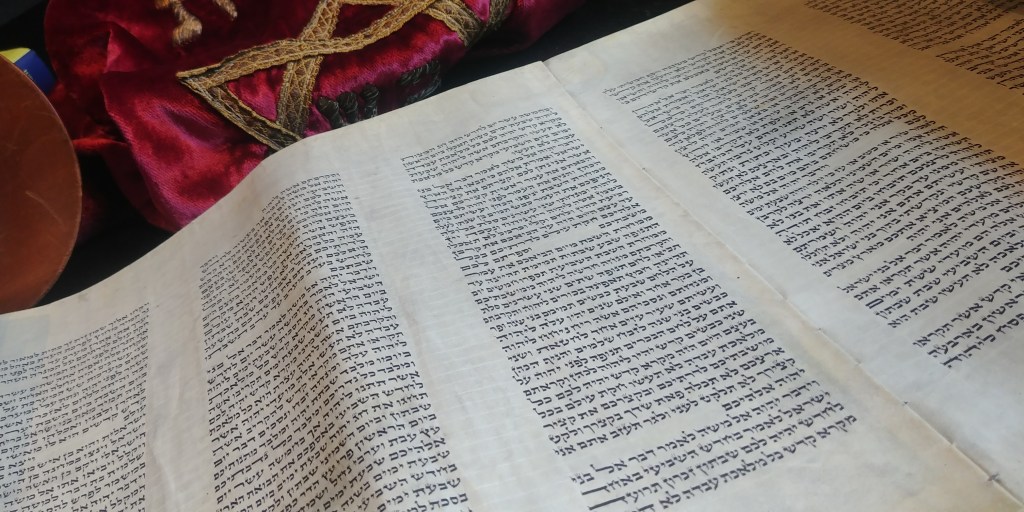

Among the texts from the Jewish bookshelf to which I most frequently return is Pirqei Avot, the second-century collection of rabbinic wisdom which is included in the Mishnah, but which stands out among the other books in that six-order collection as being quite different from the rest. Almost all of the Mishnah is about laws: instructions to post-Temple Jews regarding how to live life and observe rabbinic Judaism now that there are no more sacrifices. When do we recite Shema in the evening? What types of activities are forbidden on Shabbat? May one eat an egg laid by a hen on a Yom Tov day?

But Pirqei Avot is about how to be a better person. It is about learning and teaching Torah, about being careful with your speech, and about the complexities surrounding judgment and governing. And at the end of the second chapter of Pirqei Avot comes the piece of wisdom to which I return more than anything else in our canon:

הוּא הָיָה אוֹמֵר, לֹא עָלֶיךָ הַמְּלָאכָה לִגְמֹר, וְלֹא אַתָּה בֶן חוֹרִין לִבָּטֵל מִמֶּנָּה

Rabbi Tarfon used to say: It is not your obligation to finish the work, but neither are you at liberty to neglect it.

This piece of wisdom has guided me through many challenging times. I think of it when I am pulling weeds from my garden, when I am exercising, when I am facing a particularly daunting pastoral situation, when I grieve, when I start a new project, and pretty much every day, as I face the piles of work on my desk that never seem to resolve themselves. It speaks to the challenges facing the State of Israel, and the challenges facing our nation, and of course those facing Congregation Beth Shalom.

Whenever I need to be reminded that the only way to tackle a seemingly-insurmountable project is to take a little at a time and keep moving forward, I think of this mishnah. And it helps.

I thought of this eternally-useful gem a little more than two weeks ago when I first became aware of the death of Justin Ehrenwerth, a young man who I had only met briefly, but was the beloved son and brother and uncle of members of Beth Shalom.

Justin was only 44, and his life was cut short by mental illness. But in those 44 years, Justin accomplished more than most of us do in a lifetime. He studied at Colby College, Oxford University, and Penn Law. He worked for John Kerry’s campaign for president, and then for Barack Obama’s campaign, and then in the Obama administration. He established and ran the government agency responsible for cleaning up the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. He became the president of The Water Institute, a New Orleans-based nonprofit dedicated to solving major environmental challenges. (Our member Jordan Fischbach, who was Beth Shalom’s Vice President for Synagogue Life until this past week, was one of Justin’s employees.)

Justin was a national axe-throwing champion and a skilled harmonica player; a devoted son, brother, father and husband, and a loyal, dedicated friend who went out of his way to be there for others. Oh, and he also served on the Board of his synagogue in New Orleans.

Justin was also a person with plans. Jordan described him as being particularly mission-driven, which is something that many of us aspire to be, but (and I am speaking here for myself) actually is quite a challenging way to live. It requires discipline and energy that few of us are able to successfully muster. And all those who knew Justin recognized that energy; he was the kind of person who lit up a room when he entered.

And this made his death all the more shocking. This young man, who had a lengthy resume of successes, who did so much good in this world and truly connected with so many people, was suffering quietly.

We laid Justin to rest last Wednesday at the Beth Shalom Cemetery, and during the hesped / eulogy, I said the following, based on a teaching I learned from my homiletics professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary, Rabbi Gerald Zelizer:

The tale of the Jewish people is filled with great figures who died before they completed the projects of their lives. Moshe Rabbeinu, Our Teacher Moses, was only able to view the Promised Land from across the Jordan River. King David set his heart on building the Beit HaMiqdash, the Temple in Jerusalem, but could not do so. Our matriarch Rachel died in childbirth while on the road to Ephrat; she neither reached her destination nor knew her son Benjamin. The Zionist visionary Theodor Herzl died in 1903 at age 44, when he had only just set in motion the forces which would yield a Jewish state 45 years later.

The number of years is not necessarily the measure of success. The successful life is not necessarily the long life. The seeds that we plant which bear fruit long after we are gone are arguably the better measure.

Our ambitions, our mission, our goals, our hopes, what we strive to be, that is what determines the success or failure of our life, and not its length. How honestly, how nobly, how totally and completely one lives, these are the true measures of who a person is.

***

When we reflect on the lives of all those whom we remember today for Yizkor, we may wish to recall that the true measure of their lives was not a number of years. It cannot be surmised from the hyphen between the dates on their memorial stones. Rather, we might want to recall how they lived, what they lived for, who they loved, and the values they strived to impart through their actions. That was who they were; those were the things that they accomplished on this Earth. And we should all be grateful for that. Even though Moshe Rabbeinu does not make it to Israel, he is still Moshe Rabbeinu. Even though Herzl will forever lie in Jerusalem, in the modern capitol of a state which he imagined but never saw, he will always be the one who made it happen.

And furthermore, we should also cut ourselves some slack. No matter how mission-driven we may fashion ourselves, no matter what goals we achieve or dreams we realize, no matter how dramatically we fail, we might place some hope in the fact that those to whom we give love and life may in fact help complete our work on Earth after we are gone.

All the moreso: לא עליך המלאכה לגמור. It is not up to you to finish the task, because really, you cannot. That is the nature of humanity.

Our tradition acknowledges that. That is one reason that we read the Torah through every year, even though every time we get to the end we see that Moshe once again fails to enter the Promised Land. We knew that was coming. And yet, Joshua, his anointed successor, makes it.

We have to be willing to live with the fact that every conversation dangles, that every argument continues in some way, that our lives are like an ongoing road trip in which we never quite reach our destination, with side roads and dead ends and occasionally getting lost.

So what can we do? We can reach out more fully and completely in love to those who need us. We can try our best to move the needle in some small corner of the world. We can aim to fulfill the mitzvot, knowing that we will occasionally miss the mark. And we can try to give to our children and grandchildren the opportunity to not finish the task as well, but also not to neglect it either.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Congregation Beth Shalom, Pittsburgh, PA, second day of Shavu’ot 5783, 5/27/2023.)