Shalom! Before you proceed, you might want to read the first installment in the “Make it Meaningful!” series, from the first day of Rosh HaShanah 5782.

I’m starting our discussion today with a simple, highly unscientific poll. Now I want you to be honest:

- Raise your hand if you feel that your Jewish education (Hebrew school, day school, or something else) was sufficient for your contemporary needs?

- Raise your hand if you wish you had learned more about your tradition and spiritual heritage?

- Raise your hand if you really have no clue what this is all about.

Well, I have some good news for you: it’s never too late. And I am going to make the case for why you should want to learn more.

And the bottom line is this: because understanding what we do and why we do it as Jews will fill your life with meaning.

Our theme this year is, “Make it Meaningful!” Yesterday, we spoke about how gathering, and in particular on this Rosh HaShanah as we oh-so-gradually emerge from the pandemic, is meaningful to us. Today, we continue the discussion with finding meaning in learning.

But first, a brief correction from last year’s High Holidays sermons. Some of you may recall that, exactly one year ago according to the Jewish calendar, on the second day of Rosh Hashanah, I told the following story, which I am going to retell right now to refresh your memory:

There is a classic rabbinic story about the mother who is teaching her son how to make a meatloaf for their Rosh Hashanah lunch. After mixing the ground beef and onion and egg and breadcrumbs and spices, she rolls up the loaf, chops the ends off and throws them away, and places it in the meatloaf pan.

The son notices that she has chopped off the ends, and, concerned about unnecessary food waste in a world in which climate change and sustainability are paramount, asks his mother why she throws the ends away.

“I don’t know,” she says. That’s how my mother, your grandmother did it.

They call the grandmother to ask. She says, “I don’t know. That’s how my mother did it.”

They call the great-grandmother to ask. She is not well; she is weak, and can barely talk. “Why did I chop the ends off?” she asks, reflecting deep into the recesses of her mind. “Why did I chop the ends off? Because the pan was too small.”

Now, at lunch after services on that day, it was pointed out to me – well, actually, I was mocked – by members of my family because, they said, I screwed up the joke. It should have been brisket, they said, not meatloaf, because of course meatloaf can be shaped into whatever shape you want, whereas if the brisket does not fit in the pan, you’re stuck.

Now, leaving aside the fact that it’s only the Jews whose family members criticize each other for telling a joke wrong, I actually think that it’s funnier if it’s meatloaf, precisely for the reason that it could be shaped, and yet they continued to slice off the ends. But hey, what do I know? I’m a vegetarian! I haven’t eaten either brisket or meatloaf in more than three decades.

I used the story to make a point about minhag, custom, that it is the customs of Jewish life, which enrich our lives as we hand them down from generation to generation. But, in a seemingly-magical feat of rabbinic re-interpretation (don’t try this at home!), I am going to take the very same joke today in another direction.

There is another angle to the story: it’s that the mother and the grandmother are only going through the motions. They do not even know why they are chopping the ends off the meat. They don’t even really seem to have thought about it. And therein lies an important message:

It’s the reason why we do something, rather than the actual thing that we do, that makes a particular custom meaningful. And in order to really understand and appreciate Jewish life, in order to gain the insight and wisdom and thereby improve ourselves through Jewish engagement, we have to know those reasons.

Perhaps one of the most depressing moments I have had as a rabbi occurred at my previous synagogue on Long Island, ironically at our annual Comedy Night. It took place on a Saturday evening after Shabbat ended, and the cantor and I had led havdalah before the comedy program, and then we left the havdalah set – the wine, the multi-wicked candle, the spice box – on the bimah. So when the first comedian came up to do his set, he looks at the ritual paraphernalia, picks up the bottle of Manischewitz, and, trying to be funny, says, “I’m not Jewish; I don’t know anything about your traditions.” Somebody in the crowd, most likely a member of the congregation responded by saying, “Neither do we.”

People laughed. But my heart sank, and although I’m sure there was a little bit of hyperbole in the sarcastic retort from the audience, the kernel of truth embedded therein reminded me of my mission as a rabbi: to teach what we do, why we do it, and how it improves your life.

For example, consider two of the most common Jewish things you do: holding a seder on the first two nights of Pesaḥ and fasting on Yom Kippur. Most likely, if I asked you why you did those things, you would probably say, “To celebrate our freedom from slavery,” and, “To afflict our souls in helping to atone for our sins.” And those would be good answers.

But if I asked, why does our tradition hold daily prayer services three times a day? Why can’t you spend money on Shabbat? Why do we have two loaves of challah on Friday night and sprinkle them with salt before we take a bite? Many of us would have to check with Rabbi Google to come up with answers. Now please believe me when I say that if you do not know the answers to these questions, or many others about why Jews do what we do, there is nothing wrong with you! You are welcome and belong here.

It’s just that the “whys” behind these traditions were not necessarily taught in Hebrew school, or maybe you missed that day because of soccer practice, or your family did not observe them. Or your family could not afford Hebrew School and shamefully no effort was made to help bridge the financial gap. Really, I barely knew what Shavuot was until I was in my 30s. And Shemini Atzeret? Fugettaboutit!

I have long been a proponent of an incremental entry, or re-entry into Judaism: that while we as a community affiliated with the Conservative movement uphold the whole kit and caboodle of Jewish life, the entire collection of 613 mitzvot / holy opportunities, the way in is clearly not to try to grab everything at once. Rather, if you intend to step up your Jewish game, you should do it a little bit at a time: Say the blessing and light candles on Friday night before sundown, paired with a moment of quiet contemplation as you separate yourself from the chaos of a busy week. Or spend a few moments to say the words of the Shema, just the first line if that’s what you know, before going to sleep, as you reflect on the day.

And why would you want to do that?

Because engaging in Jewish life – observing mitzvot, coming regularly to synagogue, keeping kashrut, setting Shabbat aside as a holy day – can improve your life, your community, and your world. While I would be hard-pressed to make the case that eating brisket, or meatloaf, can do this, I can assure you that the Jewish framework for living certainly does.

But you should not take my word for it. In order to understand this, you’ll have to learn the why.

First of all, you should know that there is a lot of “going through the motions” throughout the Jewish world. There are plenty of Jewish people who are doing Jewish things, even though they may not understand the reasoning behind them or derive any meaning from them. In fact, the Talmud (Pesahim 50b) teaches that learning Torah and the performance of a mitzvah for its own sake is more valuable than doing it for some kind of reward.

דְּאָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב: לְעוֹלָם יַעֲסוֹק אָדָם בְּתוֹרָה וּמִצְוֹת אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁלֹּא לִשְׁמָהּ, שֶׁמִּתּוֹךְ שֶׁלֹּא לִשְׁמָהּ בָּא לִשְׁמָהּ

… As Rav Yehuda said that Rav said: A person should always engage in Torah study and performance of mitzvot, even if one does so not for their own sake, as it is through the performance of mitzvot not for their own sake, one gains understanding and comes to perform them for their own sake.

The 13th-century Catalan commentator, Rabbi Menahem Meiri, writes that the one who performs mitzvot for a reward is acting out of fear, and the one who is doing so for its own sake is acting out of love, and love is surely a nobler motivation.

There are plenty of us in the Jewish world who are engaging with Judaism for less-than-ideal reasons: fear, guilt, or out of a sense of duty to one’s parents or grandparents, or without any clear sense of why at all.

Every person’s path to and with Torah is different, and all paths to and with Torah are valid. But if, says the Meiri, you can get to a place where you’re doing it out of love – for Torah, for our tradition, for our community, for yourself, for the world, for God, however you understand God – harei zeh meshubbaḥ. That is worthy of praise.

So how do you get to that place? As the Talmud suggests, the more you do something, like seeking to understand our tradition, or regular tefillah / prayer, or setting aside time to observe Shabbat with family and friends, the more likely you are to see how doing so creates more love in this world.

But let’s face it: life gets in the way. We are all busy. Tefillah takes time. You might think you need Saturdays to go shopping or mow the grass or respond to work emails that you didn’t get to during the week. It can be hard to carve out time to do Jewish, let alone explore the question of why we should.

So that is why I am going to propose the following: add a little regular Jewish learning to your life. And I’m talking specifically here about Jewish text. Let me tell you why you should do this.

Because this tradition is yours, because it can help improve your life, and most importantly, because you can.

Once upon a time, Jewish text was impenetrable if you had not studied rabbinic Hebrew for years. And Hebrew schools did not have the time or the energy to teach that, so they focused on holidays and lifecycles and prayers and songs. But the real foundation for Jewish life is the Jewish bookshelf, and that was only the domain of the scholars, men with long beards.

We failed to teach that foundation. We failed to demonstrate not only the rich, scholarly basis for why we do what we do, and the pleasure of arguing over the meaning of our texts and discovering how they can help us be better humans today.

But we are now living in a period of great democratization of Jewish wisdom. With a few keystrokes, you can learn Torah! Talmud! Midrash! Halakhah / Jewish law! Mussar / ethics! And so forth. All in perfectly readable and in some cases interpreted English! Sefaria.com is probably the best source, available wherever you have access to the Internet, but there are other sources as well. There are podcasts and blogs and Daf Yomi study groups and all sorts of paths into our tradition.

The stunning wealth of information available today is, at least in this case, a blessing! But you might need some help, and that’s what I am here for. This is what Rabbi Goodman, our interim Director of Derekh and Youth Tefillah, is here for. This is what Rabbi Freedman, head of our Joint Jewish Education Program (J-JEP) is here for. Rabbi Shugerman, our new Director of Development, is also happy to help.

We are all happy to help guide you through the Jewish bookshelf. We offer many opportunities, through Derekh in particular, to get in touch with our ancient texts, which, once you dig into them, can glow with the contemporary shine of personal meaning today, but are grounded in the weightiness of ancient authority.

And what kind of things might you learn? I’m so glad you asked!

Here are just a few of the things that we have covered in various sessions at Beth Shalom in the past year:

- We learned how to manage our anger, and why silence is key to wisdom from one of our greatest thinkers, Maimonides.

- We learned that giving tzedaqah is “psycho-effective,” that is, it not only benefits the receiver in a physical way, but also helps the giver understand that we should all be less attached to our own possessions and moreso to our own spiritual relationships, from 18th-century Rabbis Hayyim Vital and Jonathan Eybeschutz.

- We have discussed the importance of speaking up in the face of corruption, and of pursuing justice over material things, from our ancient prophets Jeremiah and Isaiah and Ezekiel.

- We have explored our need for gratitude for what we have, from the Mishnah.

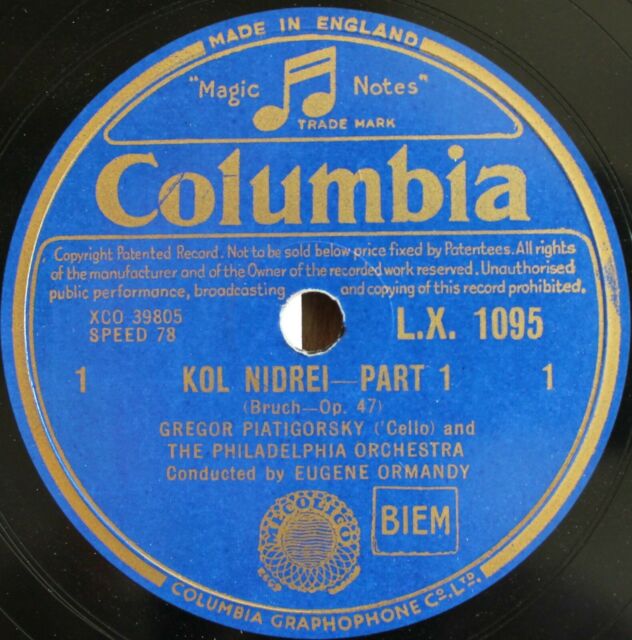

- We have learned that the essential goal of prayer is not an empty recitation of words in an ancient language, but rather an opportunity for self-judgment. That is exactly the meaning of the word, tefillah.

George Bernard Shaw is purported to have said, “Youth is wasted on the young.” It is adults who can truly appreciate how awesome and rich our people’s wisdom is. So you might have missed these things in Hebrew school. But the good news is, as Benjamin Franklin said, “The doors of wisdom are never shut.” We put a lot of emphasis on teaching children, who are not wired to appreciate the complexity of our tradition, and not enough emphasis on initiating adults into the most important mitzvah, the most essential holy opportunity of Jewish life: finding meaningful guidance in our texts.

One of the great challenges that we face as Americans is what I see over and over as a crisis of guidance. We hold in front of us the principle of freedom, and understand that to mean that everybody is entitled to make their own choices, with no judgment from others allowed. And the challenge that I see, particularly in younger people, is that we are rudderless. We may be taught how to prepare for a career, but we are not taught how to shape our relationships, to live as part of a community, to think about how our actions affect the greater good.

And that is what our tradition offers – guidance on how to be better people, how to improve ourselves and our world. “When I pray,” said Rabbi Louis Finkelstein, former Chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary, “I speak to God. When I study, God speaks to me.”

Perhaps one of the most tragic things we have experienced over the last year-and-a-half of pandemic has been the resistance by some to effective public health measures such as wearing masks and getting vaccinated. Our tradition, and the framework of mitzvot, is essentially about commitment to one another and to society, of being aware of the common good and pursuing it.

The essential meaning of living inside the Jewish framework of mitzvot is understanding that we do not function solely as individuals, that we are not merely in this to pursue only our own whims and fantasies, but rather to see ourselves in relationship to the others around us, to act on and elevate the qedushah / holiness in those relationships.

Our actions, our words have meaning; our connection with and respect for others has meaning. And when we seek that meaning through learning and living our tradition, we create a better life for ourselves, with happier, healthier relationships with all the people around us.

My challenge to you on this Rosh Hashanah is to seek meaning. Don’t be a Jew by default. That is no longer good enough in our modern American context. Seek the “why.” Discover the meaning in Jewish life by learning. Doing so will open up whole new worlds of understanding for you that will help you be a better person, offer guidance at crucial moments, and raise the qedushah around you.

Reach out to me or my colleagues here at Beth Shalom. We will set you on the path. But we will also help you take it slow. Set a goal of learning one thing – just one – in the coming year about Judaism that you did not understand: Why we pray, why we read the Torah out loud, why we say berakhot before we eat or drink, why we continue to lament the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, nearly 2,000 years ago, even if we are not expecting it to be rebuilt, and so forth.

And then, when you have learned that one thing, learn another. You’ll be glad you did. Seek the why. Make it meaningful!

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Congregation Beth Shalom, Pittsburgh, PA, Rosh HaShanah Day 2, 9/8/2021.)