Back in December, I attended the convention of the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism in Baltimore. I am proud to say that Beth Shalom was well-represented: in total, we had about a dozen attendees, which is a fabulous turnout.

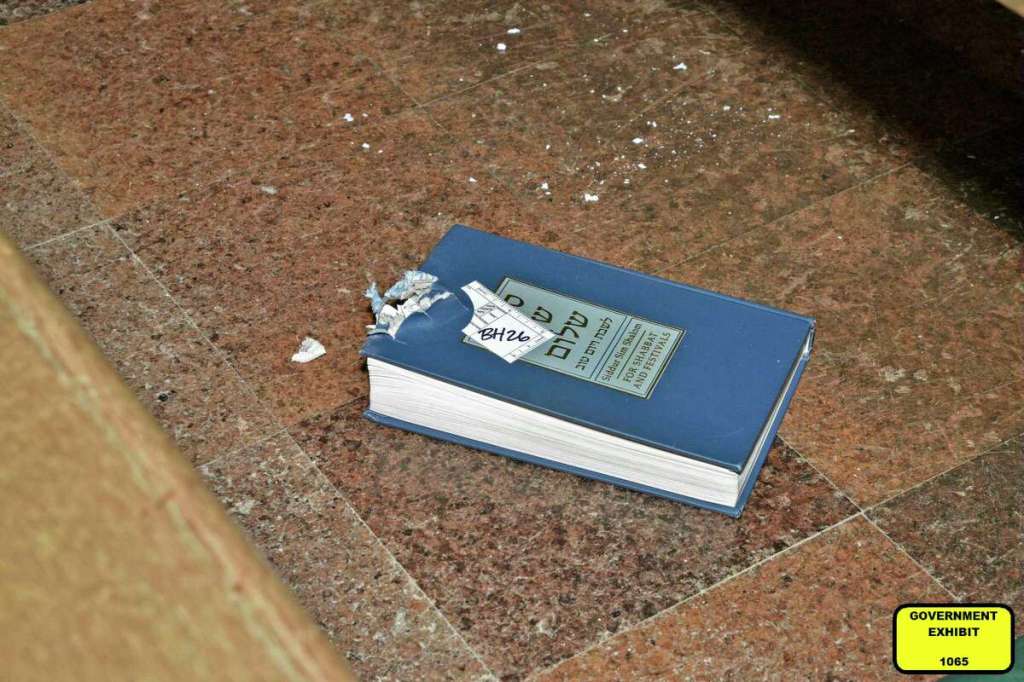

One of the sessions I attended featured a former teacher of mine from the Jewish Theological Seminary and a leading light of the Conservative movement, Rabbi Gordon Tucker. Rabbi Tucker’s talk was titled, “Does Religious Authority Speak to Us Any More?”, and he brought us textual sources about “commandedness,” that is, the knowledge that our tradition endows us with certain holy behavioral obligations.

Now, the irony here is that he was speaking to a room full of rabbis, and we toil in the trenches of commandedness every day. You may be aware that the Hebrew word for “commandment” is mitzvah, and although we often use that term in a slangy way to refer to a “good deed,” that is not an accurate translation of mitzvah. Rather a mitzvah is an action performed (or refrained from) according to our understanding of the Torah, as a part of our berit, our covenant with God.

One challenge that we face today as a people is that of motivation. Some of you might have noticed that I tend to engage with questions like these:

- Why should we keep these mitzvot?

- What is the value in gathering with our fellow Jews in synagogue on Shabbat?

- I am not clearly seeing the benefits of this berit / covenant, nor the downside of letting it go, so why bother?

The question of whether or not religious authority speaks to us today is absolutely fundamental to my work as your rabbi, and how our community understands itself. The struggle within Judaism today highlights the tension between autonomy and what Immanuel Kant, the 18th-century German philosopher, calls “heteronomy” – the idea that we are subject to some kind of motivation and laws outside of ourselves, i.e. the framework of 613 mitzvot. As modern Jews, we feel this tension between what we choose to do – autonomy – and what we know our tradition mandates – heteronomy.

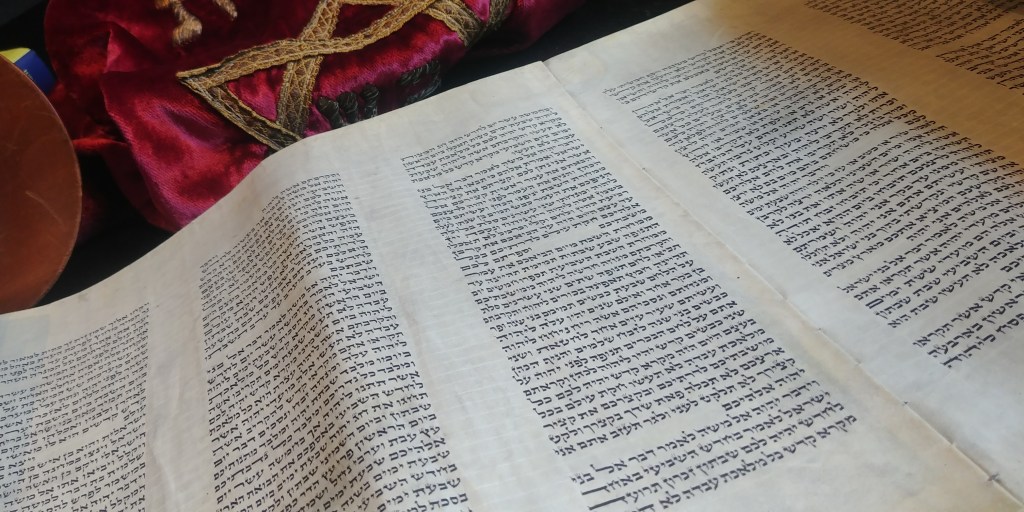

We began reading today from the book of Shemot / Exodus, and you might make the case that the foundational moment of the Jewish people as a people occurs in this book, and we will read it in a few weeks. It’s the scene where Moshe receives the Torah on Mt. Sinai, and this is the moment when the Jewish people willingly accept their heteronomy – the framework of berit and mitzvot – following their redemption from slavery. As the legal scholar Robert Cover put it in 1987 (“Obligation: A Jewish Jurisprudence of the Social Order,” Journal of Law and Religion 5:1 (1987) pp. 65-74.):

The basic word of Judaism is obligation or mitzvah. It… is intrinsically bound up in a myth– the myth of Sinai. Just as the myth of social contract is essentially a myth of autonomy, so the myth of Sinai is essentially a myth of heteronomy… The experience at Sinai is not chosen. The event gives forth the words which are commandments.

Cover does not mean “myth” the way that we often understand it, as falsehood. Rather, he uses it the way that my teacher, Rabbi Neil Gillman, taught us to understand it: a set of stories which help us make sense of our world. So the Sinai myth is the one that sets up this principle that we are commanded, that we have mitzvot to which we are obligated. Commandedness is Judaism’s concrete foundation.

Now let’s face it: speaking about “obligation” or “commandment” is difficult for us today. Our society is all about autonomy. We love choice! Some of you may recall that I have mentioned the drugstore toothpaste aisle in the past. Apparently we need 85 different types of toothpaste to choose from. But that’s trite. More importantly today, consider how we all consume news: we choose our news sources based on our approach to politics, and we all know how problematic this has become. Objective facts have become obviated by choice – we choose to understand what is going on in the world based on what we want to hear, based on our narratives. It’s all about me. It’s autonomy-squared.

Nobody likes being told what to do, or what to think, or to be limited by somebody else’s idea of how you should shape your life.

But Judaism actually depends on feeling commanded. No matter where you are on the spectrum of practice, there has to be something there outside of you that leads you to, for example, light Hanukkah candles or Shabbat candles or fast on Yom Kippur or put on tefillin or avoid eating ḥametz on Pesaḥ or sit here in synagogue listening to me. It cannot be purely social, because that is not enough of a basis on which to maintain our traditions and our communities. I suspect that if our tradition were solely based on autonomous choices, we would have faded into history with every other fashion trend. We need at least a modicum of heteronomy for the Jewish people to continue.

And from where I sit, surveying the patterns of Jewish observance today, and how that has changed in the context of the last 200 years or so, it is not too hard to see that autonomy is winning. Fewer of us are showing up to, or even joining synagogues. Fewer of us incorporate Jewish practices at home.

But the challenge that we face, as those who value autonomy, is that it is clearly getting more difficult to transmit our tradition to our children. When I was 12 years old, it was a synagogue requirement that I attend services every Shabbat morning, and my friends and I all did so. Such requirements have become more rare today, as parents and children juggle so many more options. If we were to impose such a requirement at Beth Shalom, I fear that we would lose many families, who know that they can go to another congregation with less stringent requirements for their children to be called to the Torah as benei mitzvah.

And yet, if we do not have any expectations at all – for education, for synagogue attendance, for holiday observances, for familiarity with our rituals and our texts – the Jewish landscape becomes merely a race to the bottom. “Being Jewish” becomes nothing more than just those two words, a meaningless identity.

When I was a rabbinical student at JTS, my teacher Rabbi Bill Lebeau gave me a journal article published in 1994 by economics professor Dr. Laurence Iannacone called, “Why Strict Churches Are Strong.” The article demonstrates, using data collected from a range of churches, that the greater the expectations of a faith group, the more successful the organization is with respect to commitment. That is, by setting the bar higher for religious behavior, by expecting more from your adherents, the more engaged they are, the more committed they are to the tradition, to the wisdom found therein, to the organization, to the community.

In other words, if Congregation Beth Shalom required that you attend services every Shabbat morning to be a member, or mandated regular kashrut checks of your kitchen, or even required every adult to wear a tallit in synagogue, yes, many folks would resign or be removed unceremoniously from the membership list for non-compliance. But the ones who remain would be much more highly engaged, and some who might be on the margins will work harder to meet the standard, creating a greater sense of community in our fulfillment of Jewish rituals.

Now, obviously, we are not going to do that, because we want to be a community that welcomes all who want to join, regardless of their personal observance of mitzvot. Part of the contract of choice to which we are all so committed as a society dictates that we cannot judge anybody about their choices.

But all of these ideas lead me back to one simple suggestion, one that is ancient and comes from the Talmud (BT Pesaḥim 50b):

דְּאָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה אָמַר רַב: לְעוֹלָם יַעֲסוֹק אָדָם בְּתוֹרָה וּמִצְוֹת אַף עַל פִּי שֶׁלֹּא לִשְׁמָהּ, שֶׁמִּתּוֹךְ שֶׁלֹּא לִשְׁמָהּ בָּא לִשְׁמָה

Rav Yehuda said in the name of Rav: A person should always engage in Torah study and performance of mitzvot, even if he does so not for their own sake, because it is through the performance of mitzvot not for their own sake, one gains understanding and comes to perform them for their own sake.

In other words, you may not always understand why to do a Jewish thing or why it is at all meaningful, but if you do it with some regularity, you come to appreciate those mitzvot. They become part of you. You do them lishmah, for their own sake. While putting on tefillin on a weekday morning might feel strange and uncomfortable and might mess up your hair if you are unaccustomed to it, after doing it for a while, you come to understand the meaning and value of tefillin.

Ḥevreh, the reason that the Jews are still on Earth today, that you are all sitting in this sanctuary at this moment, is that we have continued to inculcate our children with our texts, our values, our traditions. We have passed that berit, that covenant of behavioral expectations, those mitzvot on from generation to generation by teaching and learning and most importantly, doing.

Has that process always worked? No. Are there always going to be people who make bad choices, regardless of what they learn in Hebrew school? Yes.

But we must continue to expect more, to reach higher. I have been telling you all for years now that I am a “fundamentalist,” by which I mean that the fundamental aspects of Judaism – gathering for tefillah / prayer in synagogues, learning the words of the Jewish bookshelf, setting aside Shabbat as a holy day, and so forth – are what we need to help make better people and a better world.

And as a community, we must continue to uphold these standards, particularly in the contemporary way in which we do so here at Beth Shalom: in an egalitarian fashion which acknowledges the realities of the contemporary world. We cannot allow our standards to be abrogated because we perceive them to be too hard for people, or even because they may be occasionally off-putting. On the contrary, we should work harder as a community to raise the bar.

So here is a challenge: allow yourself be commanded. Seek out the heteronomy, the external motivation for reaching higher. It’s good for you, and good for the world.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Congregation Beth Shalom, Pittsburgh, PA, Shabbat morning, 1/6/2024.)