I have been a Conservative rabbi now for sixteen years, and sixteen is a great number for those who love math: it’s two to the fourth power, the base for the hexadecimal system, a favorite of computer programmers. Also, in gematria, the system of interpreting Hebrew letters through their numerical values, sixteen represents one half of the the four-letter name of God (the Tetragrammaton), which is so holy, even only the half of it, that when we represent numbers in Hebrew we don’t use the letters “yod-vav” (10+6) to represent sixteen, but rather “tet-zayin,” which is 9+7. It’s a different path to the same thing, but remarkable nonetheless. So sixteen is considered a powerful and resonant number in Jewish life.

But more importantly, I am also a lifelong Conservative Jew, and I was committed to the principles of our movement long before I could even identify and explain them.

[Read the first in the Into the Future series: It’s About Us]

Growing up in Western Massachusetts, in a fairly rural area, our Conservative synagogue felt like an extension of our living room, even though we lived 20 miles away, which for most of us seems quite far. But we knew about the Conservative teshuvah / rabbinic opinion permitting driving to synagogue if you lived too far to walk, and that was very important to us. We were a regular Shabbat-morning family, and the friendly mix of people and melodies and easygoing, egalitarian approach to halakhah was just right for us.

Some of you may have noticed that back in August, the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle hosted a poll on their website about identification with movements. It was heartening to see that 30% of respondents indicated that they identify with the Conservative movement. Now, of course that’s a totally non-scientific poll, drawing on presumably a more highly-engaged segment of the Jewish community. Nonetheless, that figure is about twice the national average of identification found in recent demographic studies. So there are still plenty of people in our neighborhood who are drawn to what we do and continue to see Beth Shalom as a source of inspiration and holiness.

And with good reason. I will totally concede my bias here, but I believe firmly that what we do in the Conservative movement still holds great appeal for many Jews, and if we could be better at explaining ourselves, many more would see that our approach to Judaism is the key to the Jewish future.

Conservative Judaism’s strength lies in its ability to hold on to our tradition but adapt to a changing world. This feature will be essential in the future, as we face rapid change.

And that is why the future of the Conservative movement is so important. And that is why we need you to be not just participants, not just members of Beth Shalom, but active ambassadors for what we do.

So what is it we do? What are the positively-articulated principles that make us not simply “not Reform and not Orthodox”? Or, as the old, totally inappropriate joke goes, not just the “hazy” between the “lazy” and “crazy.”

What makes this shul different from all other shuls?

We surveyed 100 congregants, and the top seven answers are on the board. (OK, so I didn’t have the budget for a board.)

- We are halakhic. First and foremost, we accept halakhah, Jewish law, as framing our rituals and our behavior. But we also understand that halakhic framework as being subject to minimal (i.e. “conservative”) change to reflect contemporary values. This means that our path to spiritual fulfillment reflects considered and often lenient approaches to matters within Jewish law. In doing so, we aim to ensure that our rituals and our liturgy reflect where we are today.

- We are egalitarian. All adults, including those who have been traditionally excluded from some of our essential mitzvot, are counted equally as full participants in Jewish life. For example, we call young women to the Torah as a bat mitzvah at age 13, just like the boys. This is for many of us a fundamental value, and I know from many conversations with members over the years that it is a defining characteristic that has brought many of us here.

- We are scientific. Our current body of knowledge guides our understanding of the origins of the world, and Torah, and the unfolding of our tradition over the last few thousand years. That is, while we acknowledge the Divine origin of Judaism, we also accept the undeniable evidence of the human hand in crafting and interpreting our ancient holy texts. Where science and the Torah disagree, we acknowledge that having multiple stories upon which we can draw for inspiration is in fact a strength.

- We are open to modern understandings of God. We need not be limited to seeing God only as the all-powerful yet vengeful character in the Torah who sits on a throne and metes out reward and punishment. Now, that is a conception from which we may like to draw, particularly on High Holidays, but there are many wonderful modern theologians – Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, Martin Buber, Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, Rabbi Neil Gillman – who have given us the gift of contemporary theology, enabling each of us to wrestle with God personally in a meaningful way.

- We maintain a traditional communal standard. While we acknowledge that there is a wide range of personal observance choices within our community, Beth Shalom is a building in which we keep kosher, we observe Shabbat in a traditional way, and we uphold our traditions and rituals mostly as we have inherited them.

- We believe in Am Yisrael, Jewish peoplehood, while grappling in an honest way with current realities of American Jewry, which reflect the wider palette of Americans: non-traditional families and not exclusively Ashkenazic ancestry for everyone within our view, while of course maintaining a halakhic standard regarding who is a Jew.

- We remain firmly committed to the idea and the people of the State of Israel. Like any other people, Jews have the right to self-determination in their own land. While Jews living in the Diaspora are proud and loyal citizens of their lands, the Diaspora must also be connected and invested in Israel to ensure her survival as the spiritual center of the Jewish world. And of course we are committed to our family and friends who live there, while also acknowledging the very real challenges that the State faces in managing its own future. (I will be speaking about this at length at our Kol Nidrei service.)

Those are the top of my list of our most important principles; I am sure that some of you might value another principle that is missing here, but that’s the nature of our tradition!

Each of those principles which I just outlined is at least a sermon unto itself.

But we do not have time for that, so instead I am going to share a piece of Torah as a sort of capstone to these seven principles, and I hope you will take this to heart as you step forward to be an ambassador for Conservative Judaism and for Beth Shalom. It’s from the first chapter of Pirqei Avot, the 2nd-century collection of rabbinic wisdom featured in the Mishnah:

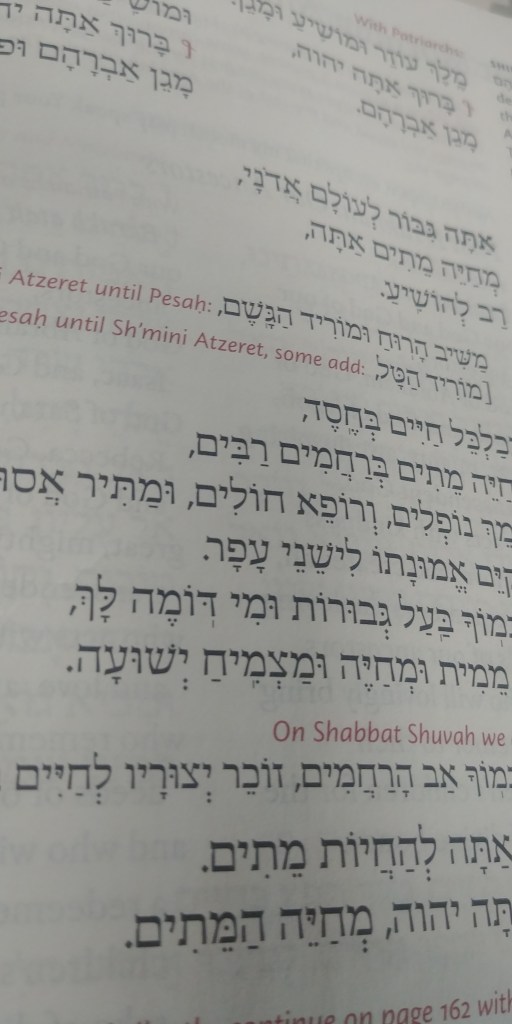

Pirqei Avot 1:12

הִלֵּל וְשַׁמַּאי קִבְּלוּ מֵהֶם. הִלֵּל אוֹמֵר, הֱוֵי מִתַּלְמִידָיו שֶׁל אַהֲרֹן, אוֹהֵב שָׁלוֹם וְרוֹדֵף שָׁלוֹם, אוֹהֵב אֶת הַבְּרִיּוֹת וּמְקָרְבָן לַתּוֹרָה

Hillel and Shammai received the oral tradition from their teachers. Hillel used to say: be like the disciples of Aaron, loving peace and pursuing peace, loving all people and drawing them close to the Torah.

This passage is notable not only because of its essential message, but also because it replaces a passage found in most Orthodox siddurim. And the fact that the Conservative movement substituted this passage about loving and pursuing peace is quite telling indeed.

You see, the way most Orthodox services unfold in the morning is that they read a series of texts about animal sacrifices in the ancient Temple in Jerusalem, which of course was destroyed by the Romans in the year 70 CE. And then they say, “May the Temple in Jerusalem be rebuilt speedily in our days.”

So at some point in the 20th century the Conservative movement decided that well, we’re just not so excited about rebuilding the Beit haMiqdash and restoring the process of sacrificing animals that ended nearly 2,000 years ago. We have prayer, which is, ultimately, a better way of reaching God.

So we took out many of those references to animal sacrifice, and substituted language which suits our values. The suggestion is that we start each day not with an imperative to rebuild the Temple, but rather to reach out to one another with the goal of peace: peace between individuals, peace between nations, and all of that undergirded with words of Torah. We respond to God’s loving gift of Torah with love; and we act on that love to pursue peace in our world.

Because what should Torah do, when applied properly? It should bring people together. It should tear down walls and cause us to make peace with one another. Torah is the source of shalom, and acting on Torah with love for our fellow Jews and our fellow people of all walks of life is the way we create a holier future.

And there is a certain irony in that passage, because Hillel and Shammai were rivals in Jewish thought. Hillel generally took lenient positions in halakhah, and Shammai took the stringent position. They disagreed on virtually every place where it was possible to disagree. And yet in doing so, they sought peace. In fact, the Talmud teaches us (BT Yevamot 13b) that despite their disagreements, the scholars in each of the opposing schools still married each others’ daughters. That is, they continued to live together and raise families together despite fundamental disagreement.

The Conservative movement seeks the path of love and peace by acknowledging that we live in a world that is quite different from the one in which the Talmud, and all the more so, the Torah were written. We see that in order to follow the path of love and peace, we have to live in this world, and not isolate ourselves. And we must also still remain in community with those with whom we disagree, to the right and to the left.

We are the vibrant center that can hold the Jewish world together. Our current climate is one which breeds division of all sorts; as the movement which occupies the center of Jewish life, all over the world, it is within our purview to reach out to find common ground.

We offer what is for many still a viable spiritual home: adherence to tradition, with a willingness to consider how the world has changed and how our tradition should change with it. Hence counting all adults as equal in Jewish law. Hence treating a marriage between two Jewish men or two Jewish women as being equivalent to that between a man and a woman. Hence understanding that taking lenient positions, like Hillel himself, strengthens our connection to our tradition and widens our tent, creating more peace.

…

Some of you know that our local Federation scholar, Rabbi Danny Schiff, published a book within the past year called, Judaism in a Digital Age, in which he declared that the moment for movements within Judaism has passed. Rabbi Schiff and I had a very spirited public disputation about the Jewish future here at Beth Shalom last winter. I’m a movement guy, by which I mean that I believe that institutions such as the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism still hold a good deal of value as a “brand” within the Jewish world. And I am proud that we are affiliated with the movement.

Beth Shalom has emerged from the pandemic not just unscathed, but also with a path forward for sustainability, including the $1 million matching grant for redevelopment from the State of Pennsylvania.

We have successfully launched the Ḥavurah program, which connects members of our congregation in small groups for social activities, and I am certain it will help build more connections in our community, to make Beth Shalom more highly integrated. (By the way, if you missed joining, it’s not too late! Be in touch with our Executive Director, Robert Gleiberman, and we’ll connect you with other Beth Shalom members like you.)

All of that is wonderful, but it is not enough. The future of Beth Shalom, and the Conservative movement, depends on you. It depends on your willingness to commit yourself not only to belonging, but also to showing up. To take advantage of everything that we do here, and to take it home and make it a part of who you are and how you live.

Now of course, stepping up your involvement may seem daunting. Where do you start? How about coming to see me to talk about how to engage more in Jewish life and your community. I am happy to help you craft a path to enriching your Jewish involvement so that you and your family may benefit more handsomely from everything that Jewish living offers.

And trust me on this: your investment of time and energy and resources into Beth Shalom will be worth it. In being more deeply connected to our tradition and to each other, you will gain a sense of kedushah / holiness, of groundedness which will carry you confidently into the future.

So what will make the future of Beth Shalom and the Conservative movement brighter? Of course there are the essential principles I outlined above, which we must continue to uphold and value – I take those things as a baseline. But here are some other things we will be addressing, moving forward:

- Complete egalitarianism with respect to ritual practice. As with all transitions within institutions, change is slow. So while many women in our congregation have embraced the mitzvah of wearing a tallit during morning services, and a small number fulfill the mitzvah of tefillin, we still have a long way to go to ensure that all feel welcome and indeed obligated to participate fully in the time-bound mitzvot which have traditionally only been incumbent upon men. This is an active conversation at the Religious Services Committee.

- Telling our story. We need to be able to positively articulate why we do what we do. That is precisely why I gave you the list of seven essential principles today. Having that language available will make you a better ambassador for Beth Shalom, which will lead to a more sustainable future for this congregation. Feel free to cut and paste from above! You need to know this, and you need to be able to share it with others. Our story, our values, our principles, have real value that we must continue to broadcast to the world.

We also have to tell and retell our story as a congregation, particularly as we enter the upcoming capital campaign. Our future will depend on our being able to describe where we have been and where we are going, and we hope to engage all of you with that as we move forward. - Increased interconnectedness. The Ḥavurot are just one means. The more you come to Beth Shalom – for services, for programs, for lifecycle events – the more that you will feel ownership and connected to others. Just about everything we do includes food and schmoozing opportunities – there is a reason for that! We want you to feel like you are an essential part of this community, that this is your shul, that I am your rabbi.

We have the ability, as the ideological center of the Jewish world, to hold us all together. We are a model for living together even in the face of disagreement, for peace and love in Torah. And the world needs that now, more than ever.

So go out there and be an ambassador. That will ensure a healthy future for the Conservative movement, and for the rest of the Jewish world as well.

And here is one way you can do so: Rabbi Shugerman and I and a few other lay leaders and staff will be headed to the USCJ Biennial convention (which, for unexplained reasons, they are calling a “Convening” this year) in Baltimore from Dec. 3-5. It will require an investment of time and money, but every time we send a delegation to this convention, we come back with new ideas which help us be a better congregation. If you’re thinking about it, come talk to me. We would love to have you join us.

A final note from the Mishnah I quoted above. The text reads:

אוהב שלום ורודף שלום

Ohev shalom verodef shalom. Loving peace and pursuing peace. Those are two different things! It’s not enough merely to love peace; you have to go out there and make it happen. Likewise for the future of Beth Shalom: it will not be enough for us merely to appreciate Conservative Judaism. Rather, we have to continue to practice it, support it, and spread the word.

Shanah tovah!

Next in the series:

Kol Nidrei: The Future of Israel

Yom Kippur: The Future Must Be Human