I received a call from a good friend last week: my colleague and former senior rabbi on Long Island, Rabbi Howard Stecker. He was wondering how our community was reacting to the trial in Pittsburgh of the 10/27/2018 Tree of Life attacker.

And the truth is, I was not sure how to answer. I have reached out to the members of Beth Shalom who have testified or will soon, and for them this is a particularly emotional time. I have discussed with a few folks who are certainly feeling the gravitas of this moment, including some who are taking the active decision not to read the news. There is at least one person in my orbit who is quite distraught, and has been so since the day of the attack.

But my sense is that our reaction is, on the whole, somewhat muted. Everybody knows it is going on, but at least as far as I can detect, we are, emotionally and spiritually, in a much better place than we were in the months following the shooting. Thank God.

I suspect that many of us have by now built up good defenses that enable us to feel and grieve the losses of that day, but not allow ourselves to slide back into the depths of the trauma of 4½ years ago. Contrary to expectations, extremist protesters supporting the defendant outside the courthouse have not materialized. And for that I am grateful.

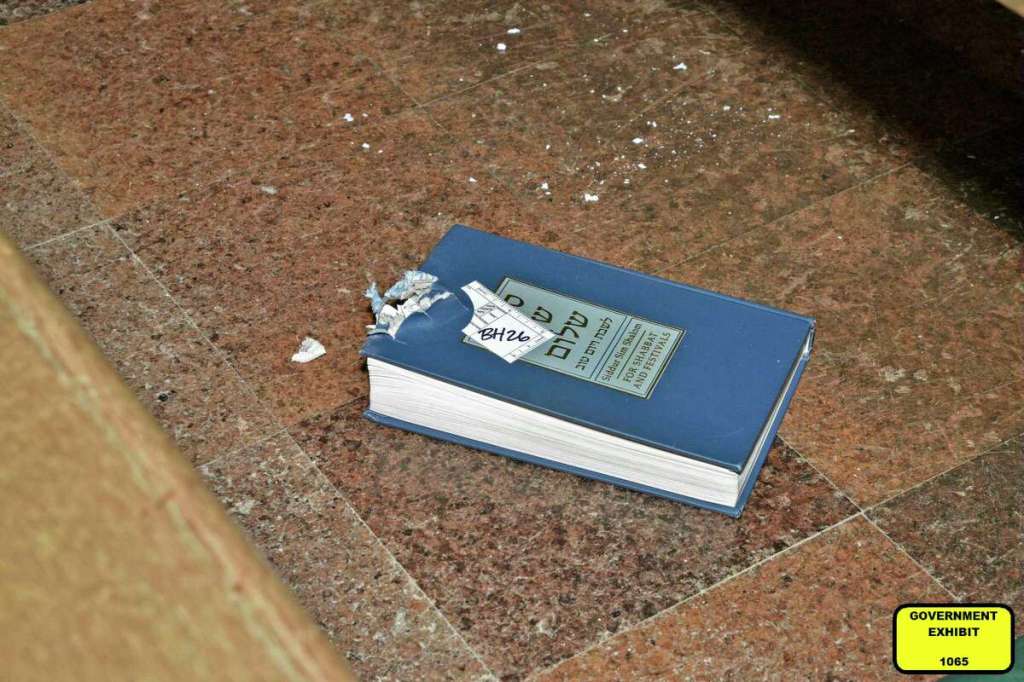

I have been skimming reports in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette without reading too closely. I did see the photo of the Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat and Festivals (the dark blue one) which Rabbi Jeff Myers took with him from the building; it has a bullet hole on the top. I hope that siddur ends up in the Rauh Archives, if not some other museum that is a testament to the survival of the Jewish people.

Rabbi Stecker asked me, as you might imagine, about the death penalty, about how folks in our community feel about it, and of course I told him that we are divided. We certainly have members of this community who are vociferously against, and some others who are decidedly for, and probably many of us who are uncertain exactly where we stand.

I have certainly thought, at many points in my life, that the death penalty is wrong, that the only figure in our world with the authority to issue and carry out execution, to actually end a human life, is God. I must concede, however, that this case gives me pause.

Now, you might think that the logical thing for a rabbi to do in this case is to go to the Jewish bookshelf for an answer. And the answer, as you may imagine, is not so simple. So I would like to add a brief caveat at this point:

My role as rabbi is not to tell you how to think. My role, rather, is to complicate the discourse by adding depth, to provide you with traditional tools from the Jewish bookshelf. A rabbi is a teacher of our religious tradition, and our sources demand that we consider challenging issues from multiple perspectives.

The Torah is clearly in favor of the death penalty. Not just in favor, but let’s put it this way: the phrase, “mot yumat,” “he shall be surely put to death” for some crime occurs at least 31 times in the Torah; it is mandated for such crimes as violating Shabbat (Ex. 31:15), adultery (Deut. 22:22), and of course first-degree murder (Ex. 21:12-13). There is also the famous case of the “ben sorer umoreh,” the wayward and defiant son, who is to be stoned to death by the men of the city (Deut. 21:18-21). For the record, we do NOT put anybody to death these days. (So our bar mitzvah boy and all of his friends can relax.)

One theory about these punishments is that the original meaning in many of these cases is not execution by human hand, but rather by God. See e.g. the explanation by Rabbi Ishmael, Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 84a, which indicates that in the case of a non-kohen who approaches the altar (Numbers 18:7), mot yumat; R. Ishmael asserts that this execution is “biydei shamayim,” by the hand of heaven.

But the ancient rabbis, who arrive on the scene many centuries after the Torah was completed, engage with the question of the death penalty in a more nuanced way than the Torah itself. On the one hand, they did not eliminate the death penalty, but on the other, their agenda is clearly to ensure that it is rarely, if ever, applied. The Talmud insists, in capital cases, on careful selection and questioning of witnesses, of requiring 23 judges instead of the usual three, and other ways to set the bar so high such that almost nobody would ever be executed.

And perhaps one of the best-known mishnayot on the subject, Makkot 1:10, says the following:

סַנְהֶדְרִין הַהוֹרֶגֶת אֶחָד בְּשָׁבוּעַ נִקְרֵאת חָבְלָנִית. רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בֶּן עֲזַרְיָה אוֹמֵר, אֶחָד לְשִׁבְעִים שָׁנָה. רַבִּי טַרְפוֹן וְרַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אוֹמְרִים, אִלּוּ הָיִינוּ בַסַּנְהֶדְרִין לֹא נֶהֱרַג אָדָם מֵעוֹלָם. רַבָּן שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן גַּמְלִיאֵל אוֹמֵר, אַף הֵן מַרְבִּין שׁוֹפְכֵי דָמִים בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל

A Sanhedrin that executes a transgressor once in seven years is characterized as a destructive tribunal. Rabbi Elazar ben Azarya says: This applies to a Sanhedrin that executes a transgressor once in seventy years. Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Aqiva say: If we had been members of the Sanhedrin, no person would have ever been executed. Rabban Shim’on ben Gamliel says: In adopting that approach, they too would increase the number of murderers among the Jewish people.

In other words, the Sanhedrin should be guided by the principle that it should carry out the death penalty exceedingly rarely, and the opinion of Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Aqiva, who would rather not execute anybody, is countered by Rabban Shim’on ben Gamliel, who suggests that the death penalty should remain as an option because it is a deterrent.

And, consistent with the mishnah, an Israeli court has only handed down the death penalty exactly once in its 75 years of existence. A tribunal in Jerusalem convicted and sentenced to death Adolf Eichmann, the architect of the Nazi “final solution,” in 1962.

Regarding the trial in our midst, Rabbi Danny Schiff wrote the following, which appeared in the Chronicle on May 10:

The classic ethos of Judaism would not contend that there should be zero executions in America. But it would also posit that the number of executions should not be far distant from zero. Eschewing absolutist positions, Judaism advocates a path that is capable of confronting the worst evil imaginable but does not hold that every heinous crime fits that description.

We must ask ourselves: Given that Judaism wants the death penalty to be rare, does this case rise to the level in which the death penalty is warranted?

There is some small part of me that wants to say, absolutely yes. Yes to Eichmann. Yes to Osama bin Laden. Yes to this person who was so filled with hatred for us, for our people.

And that voice is hard to hear over the din of other voices, which remind me of the Sanhedrin, of Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Tarfon, or of my own personal feeling that maybe even this one is also biydei shamayim, in the hands of heaven. But I also know that in cases like this, we, the Jews, must defer to the law of the land. As my colleague, Rabbi Abigail Sosland, writes in her essay, Crime and Punishment (in The Observant Life, ed. Martin S. Cohen, p. 467):

The concept of dina demalkhuta dina [“the law of the land is the law”] cannot be ignored and the requirements to convict or acquit need not – and, in the secular justice system should not – come directly from the rabbinic sources, but from the secular law of the land. Still, the values of Jewish tradition, the level of deliberation with which the rabbinic courts were to handle death penalty cases, and their sense of grave responsibility should still inform our participation in such matters.

So how do I feel? I am praying right now that the jury considers the evidence thoroughly, that the attorneys make their cases thoughtfully and honestly, that the witnesses report details faithfully for the record, that the judge ensures that justice is carried out appropriately, that nobody will have any basis on which to say that the defendant did not get a fair trial.

And I am also praying that I will never be faced with the question of life and death in a way that is so completely real.

But perhaps most importantly, I want us all to remember that the focus of Judaism is life. That we are gathered here today to celebrate Shabbat, which is a reminder of the creation of life; that we called a young man to the Torah today, marking a new stage in his life; that we celebrated a bride and groom who will be married tomorrow, in a fundamental affirmation of life.

That when we say recite the words of Qaddish, in remembrance of those whom we have lost, and in particular in remembrance of those who were so brutally taken from us just down the street 4½ years ago, we recall that those words too are not about death but also an affirmation of life, that we must carry and uphold their names and their spirits as we continue to embrace life.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Congregation Beth Shalom, Pittsburgh, PA, Shabbat morning, 6/10/2023.)