Context matters. In fact, the way that we understand Judaism – our history, our rituals, and our textual heritage – here in the Conservative movement, is based upon this very principle. We never read our sacred texts or discuss Jewish law or ritual without context, both ancient and modern.

One simple example is the Amidah, the standing, silent prayer mandated by our tradition at least three times each day (four times on Shabbat!). You may know that there is no commandment in the Torah to recite the Amidah. However, when the Romans destroyed our Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE, they put an end to the sacrifices, which ARE described in the Torah. Our rabbis decided that in this new context, daily recitation of the Amidah would take the place of those sacrifices.

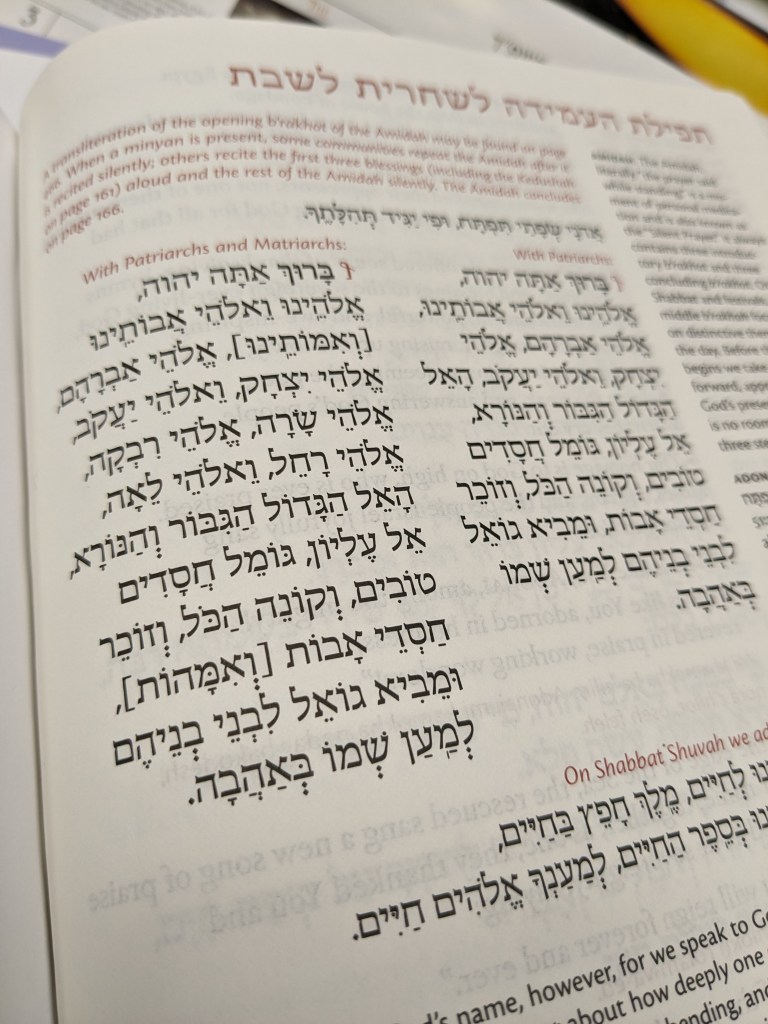

And it requires even more context to understand why we invoke not only the Avot of our tradition, the Patriarchs, in the opening line of every Amidah, but also the Imahot, the Matriarchs as well. That is an innovation of the last few decades, an acknowledgment that we also look to the women of our ancient story as well for values and guidance. And it took the context of understanding women and men to be equals in Jewish life for this change to occur.

Our tradition has unfolded over thousands of years, and we always read our texts in the context in which they emerged, and our practices today must reflect our current situation.

Academics know that context matters. It is essential to understanding our world, our history, our cultures.

And yet.

There are some times when the invocation of “context” requires context. When presidents of three universities, when pressed on the question of whether protesters chanting certain anti-Israel and anti-Jewish slogans was permissible speech on campus, they deflected with, “It depends on the context.”

***

Ḥevreh, I must say that I’m just not shocked any more – not about the dramatic rise in anti-Semitic incidents in America, not about the insecurity Jewish students are feeling on campus, not about how many Jews feel that they have been abandoned by their political allies, not about how the American media covers the conflict in Israel.

I’m just not shocked any more.

But I am just a tiny bit surprised that the presidents of Harvard, MIT, and Penn publicly failed in unison to concede that language calling for the killing or displacement of Jews meets their campus standards for bullying or harassment.

The presidents, who responded with legalese when an honest, personal reckoning with the fact that people screaming “Intifada” are, in actuality, calling for the death of Jews. That is what that word meant when it was happening in Israel two decades ago.

And of course they issued apologies for their poor choice of words after the fact, and one of them is no longer a university president. But in the moment, when the spotlight was on them, they failed. When it really counted, they should have been there with the right answer, which is, “Calling for the killing of Jews is wrong under any circumstances. It does NOT depend on the context.”

And they totally, absolutely missed the point, which is that Jews all over America and the world, but most acutely on university campuses, are feeling the rise in anti-Semitism quite personally. The evident double standard here is that in recent years these campuses have gone far out of their way to accommodate the feelings and sensitivities to language of Black, Hispanic, Native, LGBTQ, Asian students and faculty in various ways. Even the slightest discomfort in this regard has caused university leaders to react vigorously and punitively.

But somehow, when it comes to Jews, our feelings do not matter. Anti-Semitism, in the minds of some, is just not enough of a thing. Jews are apparently too “privileged” for university administrators to bother with. When protesters call for “any means necessary,” which implicitly supports the brutalities of Hamas, is that not an actionable offense?

Even if, as a recent poll suggests, less than half of those marching for Palestine know which river and which sea they are referring to in one well-known chant, does the implied destruction of the State of Israel not threaten Jews?

Today in Parashat Miqqetz, we read a captivating moment: it occurs when Yosef’s brothers have come before him with their hands out, seeking food, and of course they do not know that they are standing before the brother they sought to kill many years earlier. And they are speaking to each other in Hebrew, and Yosef, who remembers the language of his youth, can understand them, but they are unaware.

We understood loud and clear what these representatives of the most prestigious universities in the United States were saying, and they had no idea. What they were saying, by referencing “context,” was, we are afraid.

We are afraid that if we admit on the record, before Congress, that “From the river to the sea,” or “Intifada” are anti-Jewish statements, that we will be called out by our allies. We are afraid, because while it is OK for Jews to be fearful, to cower in their dorm rooms, to be harassed on campus, it is definitely NOT OK for any member of any other persecuted group, and we definitely don’t want to anger any of those folks.

Ḥevreh, we, the Jews, cannot be afraid. We cannot allow ourselves to be bullied.

On the contrary, we have to hold our heads up high, to stand proudly with the people and the State of Israel, to stand with and for each other, and to keep doing what Jews have been doing for thousands of years – that is, carrying out the mitzvot / holy opportunities of Jewish life.

Some of you were here last week when Rabbi Mark Goodman taught a couple of Hasidic texts about the pit into which Yosef’s brothers had thrown him, back in Parashat Vayyeshev. One of those texts put forward a fascinating idea, one which we can absolutely draw on today. Rabbi Shemuel Bornsztain, the late 19th-early 20th centure Sochatchover Rebbe, wrote that it is our commitment as Jews to God’s covenant which maintains the presence of the Tzelem Elohim, the Divine Image, within us. When we fail at that covenant, the Tzelem Elohim disappears, and then we are on our own – that is, we are subject to the dangers of the world around us.

Framed more positively, our fulfillment of Jewish life – ritual, prayer, text learning, the mitzvot which highlight the holiness in our relationships – protects us and insulates us from danger. Our secret to survival is not the Anti-Defamation League, which is only 110 years old, although of course they do very important work. The reason we are still here is that we have maintained our spiritual heritage through millennia of persecution. When we merit the presence of the Tzelem Elohim, we have nothing to fear.

Something else happened nearly two weeks ago, which did not shock me, but certainly made me feel just a wee bit unnerved. Roughly 500 anti-Israel protesters showed up outside a kosher falafel restaurant in Philadelphia to charge the owner of the restaurant, our son of Pittsburgh, Michael Solomonov, with “genocide.” Will all those of us who are supportive of Israel soon be subjected to angry mobs?

I have heard from a friend who works for Hillel International, the center for Jewish life at colleges and universities, that the situation on American campuses for Jews is actually much worse than what you might hear on the news. It’s not necessarily the high-profile anti-Semitic incidents, like the one that happened at Cornell a month ago, but the subtler remarks, the low-level incidents, the constant barrage of anti-Israel language on social media and chanted on campus. It’s the pressure to concede to the pro-Palestinian narrative of Jews as oppressors, of the collective guilt of all Jews.

I am relieved to be able to say that we have not yet arrived at the equivalent of Kristallnacht, in November of 1938, when Nazi thugs across Germany destroyed synagogues and Jewish-owned businesses. Thank God.

But should we be concerned? Absolutely. Should we be reaching out to our elected officials? Yes, constantly.

And even more so, now is a crucial moment in Jewish life: a mandate to up our game. We need to double down on the formula which has held us together as a community in spite of the Romans, the Babylonians, Antiochus, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, and on and on. We must continue gathering in synagogues for prayer. And kindling lights. And teaching our children the words of our ancient tradition, and the contexts in which they emerged. And upholding all of the traditions which have maintained Tzelem Elohim – God’s image – within each of us.

Context matters, and in our current context, the spiritual framework which has guided and nourished and protected our people for the entirety of our history still works. And we need that framework today, more than ever.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Congregation Beth Shalom, Pittsburgh, PA, Shabbat morning, 12/16/2023.)