I was in church last Sunday. It was the first time in many years that I had been to church for a Sabbath service. Our dear friend and teacher Rev. Canon Natalie Hall invited me to participate in the service at the Church of the Redeemer (Episcopalian) in Squirrel Hill, where I led the congregation in the English recitation of Psalm 121, and sang with them (in Hebrew!) the first verse: Esa einai el heharim, me-ayin yavo ezri? I lift up my eyes to the mountains; from where does my help come? My help comes from Adonai, the Maker of Heaven and Earth.

As many of you know, Pastor Hall and her family were here with us last Shabbat to show their support and solidarity with our community in the context of the immense grief and loss we have felt for the last two weeks.

It is good to have friends.

You know who had no friends? Noaḥ. You know how we know that? Because in the first verse of the parashah, Bereshit / Genesis 6:9, the Torah says, אֶת־הָֽאֱלֹהִ֖ים הִֽתְהַלֶּךְ־נֹֽחַ, generally understood to mean, Noaḥ walked with God. But that is because, as the only somewhat righteous person in an evil generation, he had no friends. The 15th-century Portuguese commentator, Don Yitzḥaq Abarbanel, observes that:

והיה זה לפי ש”את האלהים התהלך נח” רוצה לומר שעם היות שדר בתוך רשעים לא הלך בדרך אתם אבל נתחבר ונדבק אל האלהים לא נפרד ממנו כל ימיו

… and so it was that Noaḥ walked with God, that is to say that despite the fact that he lived among wicked people, he did not walk on their path with them, but rather was bound to and cleaved to God, and was not separated from God for all of his life.

The Hebrew word for “friend,” ḥaver, has the same root as the word that Abarbanel uses for “bound”: נתחבר / nitḥabber. Noaḥ’s only ḥaver, was God; he was bound to God because he had no other friends. And that is further reinforced by the fact that for all the time he and his family spent on the Ark, they did not seem to pine for other humans. They never had friends among the people with whom they lived.

With the shining examples of Pastor Natalie Hall and her husband Rev. Dan Hall and the Church of the Redeemer excepted, I must say that I am not exactly feeling the love right now from the people around us. Where are the allies? Where are all the righteous gentiles standing up for the Jews? Where is the unequivocal condemnation of the unconscionable, horrifying murder, abuse, and kidnapping of Jews by thousands of Hamas terrorists? Where is the non-Jewish outcry regarding the greatest pogrom since the Nazis?

Do you remember, after October 27th, 2018, when Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall in Oakland was standing-room only, and a sea of umbrellas stood outside as well, to grieve together in memory of our qedoshim, the beloved members of our community who were brutally murdered by an anti-Semitic terrorist? Do you remember seeing the huge group of local clergy on that stage? Christians and Muslims and Hindus along with the Jews.

And do you remember when the whole world erupted when a Minneapolis police officer knelt on George Floyd’s neck for 8-½ minutes, murdering him? All over the country, people marched and knelt down on one knee and screamed for “justice.” I gave four sermons about it. Late night comedians could barely crack a smile for weeks.

And now, 1400 Jews are dead; thousands more injured, physically and emotionally. Israelis are living in bomb shelters. Shoah survivors and children kidnapped. 200 are hostages. Hostages! Young women taken captive were paraded as trophies, and much worse. I have avoided watching these videos, but they are out there.

Where are the voices condemning Hamas?

Where are the voices calling for regime change in Gaza?

Where are the voices crying out for the release of the hostages?

Why is there NOT outrage when Palestinian deaths are caused by Hamas?

Why leave it to Israel to do the dirty work of removing Hamas?

Why make Israel suffer alone the consequences of the horrific body count that is unfolding as Israel defends herself through eliminating this malignant cancer on humanity?

Why blame Israel for civilian casualties, when Hamas places their people in harm’s way?

And where, oh where are all the well-meaning people marching for justice for Israel?

Why is nobody calling out, “Defund Hamas,” or “Defund Iran”? Gaza has received billions of dollars in the last 16 years from the international community. Where has that money gone? Not to the people of Gaza.

What happened to the moral clarity of the university presidents who have made embarrassingly pareve statements?

America’s greatest ally is sitting shiv’ah, a thousand times over. How hard would it have been merely to say, We decry the brutal murders of 1400 Israelis, Americans, French, Thai citizens, and so forth? How difficult is it to stand unequivocally against terrorism? To say that we who stand up for every kind of underdog in the world, every oppressed individual, we stand with the Jewish people at this moment of pain and grief.

But no. What we got were mealy-mouthed, half-mumbled, half-statements about protecting all life in the region. And the Ivory Tower has turned into a Petri dish of anti-Semitism. Over 30 student groups at Harvard University who said, “We, the undersigned student organizations, hold the Israeli regime entirely responsible for all unfolding violence.” No mention of Hamas.

We got the professor at Cornell, my alma mater, who was “exhilarated” by the attack on Israeli civilians, stating “Hamas has challenged the monopoly of violence.” Just to be clear, he was saying that Israel holds the monopoly of violence, and he was proud that Hamas took the reins by mutilating Israelis in their homes, by dragging them through the streets.

To be fair, we have a few bold leaders who have said the right things.

Thank God for President Biden and French President Emmanuel Macron, who said all the right things. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and British PM Rishi Sunak went to Israel this week to offer support. Thank God for Lt. Gov. Austin Davis, who addressed the Federation’s Vigil for Israel on Thursday evening, and for PA Senators Bob Casey and John Fetterman, who have been unwavering in their support.

Thank God for Pastor Natalie Hall. And Russ Cain, our occasional security guard, who, when he saw us at the first Federation gathering, gave Judy and me a big hug, tears in his eyes, and told us he was praying for us, and for my son.

But I’m not feeling very supported outside of my Jewish circle. And I fear for what the future holds. How many friends do we really have?

OK, so our tradition teaches us to give kaf zekhut, the benefit of the doubt. Maybe there was no fierce condemnation of Hamas or terrorism or rape or kidnapping or torture because Israel is just too complicated.

- Maybe it is because some see the Jews as “privileged.”

- Maybe it is because of the misinformed impression that a reductive body count is the sole indicator of who is to blame and shove Oct. 7 into the specious trope of the “cycle of violence.”

- Maybe it is because some people simply cannot see the hypocrisy of denying that Jews are indigenous to the land of Israel, believing instead in some sort of insulting and woefully myopic narrative that Israel is the aggressor here, that “colonizers” are carrying out “genocide.” As if Israelis could simply pick up and return to Poland, Iran, Yemen and Ukraine.

- Maybe it is because the agenda of those committed to so-called “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” somehow excludes Jewish suffering due to anti-Semitism.

Whatever the reasons, I am looking around and wondering where our friends are. And I wish God would send us an Ark, because very soon there may be a torrential downpour of criticism of Israel as they try the best they can to dismantle Hamas, the very source of violence, the enemy of Israel and indeed the people of Gaza.

At this point, I would like to make sure that I offer you something more than righteous indignation. What can we do, from so far away?

- Call / email / text your friends in Israel to express your support/condolences/grief etc. The same for the people in your neighborhood whose children and grandchildren are there right now, serving in the IDF and throughout Israel.

- I do not generally advocate for the use of social media for stuff like this, but when you see people saying grossly inaccurate or completely unfair statements, you have a duty to at least try to state the truth. If we let the social media spaces become sewers of Jew Hatred, that will be on us.

- Write and or call your elected officials. Thank those who have been honestly and forthrightly supportive of Israel and the Jewish people. Demand that they help keep up political pressure to bring home the hostages.

- Let your supportive non-Jewish friends and neighbors know how you are feeling at this time. To share with them your sense that this attack was felt by the whole Jewish world, that we are in pain, and we want to know that you are with us and for us. I know that is not so easy to do, but it helps spread the word among the wider population that the Israeli people are important to us here in America.

- Donate to the Federation’s emergency relief fund for Israel. The Jewish Federations of North America have set a goal of raising $500 million for emergency relief for Israel; they have already raised $380 million, $5 million of which has been pledged in Pittsburgh. Every dollar helps.

Ḥevreh, I am anxious about the future, about the near term and the long term. I want Israel to continue to thrive, and I want a just political arrangement for all people on that tiny, yet emotionally-wrought piece of land. I want peace. And let me be clear: we must also pray for peace for all the inhabitants of that land. But I also know that the forces of terrorism will not bring peace; they will only bring more terrorism.

And as we continue to pray for Israel, let us hope that our friends find the courage to stand with us.

~

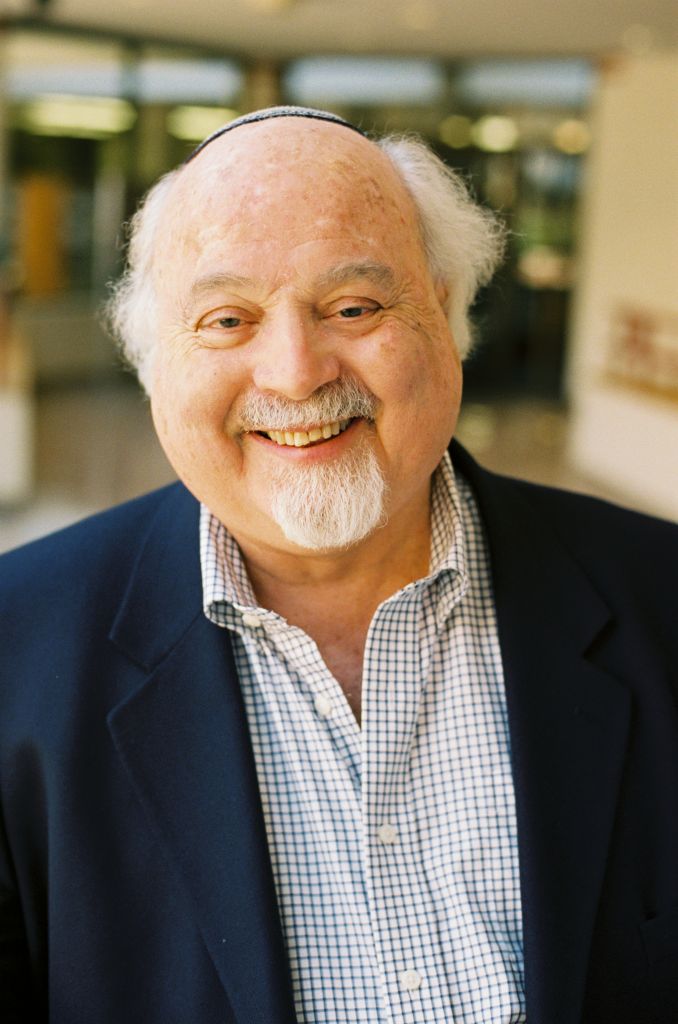

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Congregation Beth Shalom, Pittsburgh, PA, Shabbat morning, 10/21/2023.)