I have always been a peacenik, and I suspect that many of us here are fellow travelers in that regard. Not a lot of jingoists here at Beth Shalom, I think.

Let me say this right up front, so that this message does not get lost in what follows:

- I believe that the only sustainable path for Israel, once the war is over, is to continue to pursue the two-state solution.

- I believe that all Israelis, Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Druze, Circassians, deserve to live in peace, unmolested by terror.

- I also believe that Palestinians deserve to live in peace as well, in their own democratic nation, governed by legitimately elected, non-corrupt leaders.

- And I believe that this can only happen if the terrorist group Hamas is dismantled. There is no co-existence with Hamas.

***

The birkon (which some refer to by the Yiddish word “bencher” – the little book that contains a few prayers and songs used at mealtimes) that we use at our home includes the following addition in Birkat HaMazon, the so-called “Grace after Meals”:

הרחמן הוא ישים שלום בין בני שרה לבין בני הגר

May the Merciful One bring peace between the children of Sarah and the children of Hagar.

You remember Hagar, right? We met her today in Lekh Lekha. She is Sarah’s handmaid, and as Sarah has difficulty conceiving, she allows her husband Avraham and Hagar to have a son together, whose name is Yishma’el. In next week’s parashah, Vayyera, Hagar and Yishma’el will be sent out of Avraham’s house, albeit with the blessing that Yishma’el will be the father of a great nation, which both the Torah and the Qur’an read as the Arab peoples.

So that line in the birkon is a request for peace between the Jewish world and the Arab world – the children of Sarah and the children of Hagar.

I have always tried to remind myself, in times of war in Israel, that our tradition sees the Arabs as our cousins, that our struggles over the Land of Israel are in some sense a manifestation of an ancient family rift that is hard-wired into Middle Eastern culture and politics, a postulate of the region.

And, as a spiritual leader for the Jews, I also have to remind myself that my primary allegiance is to the Jewish people. Maimonides speaks of concentric circles of responsibility; we are responsible for those closest to us first beginning with ourselves, then our immediate family with the circles expanding outward. And the Jews are the people closest to me.

No matter how much I like to see myself as a citizen of the world, as one who cares deeply about all the people around me who are not members of our tribe, I am proud of my Jewish heritage, honored to be a tiny link in a chain which stretches back millennia, and steadfast in my belief that the Jews bring light and wisdom and peace into this world. The Torah narrative follows Avraham’s second son, Yitzḥaq, not Yishma’el, and so my first responsibility is for us.

At this moment, when the whole world seems to be screaming about Israel’s misdeeds, it is extraordinarily important to remember who we are and where our commitments lie. We need to be forthright in standing together as a people, and to stand in particular with our people in Israel.

And standing with Israel does not mean that we are permitted to be indifferent to the suffering of innocent people in Gaza who have been placed in harm’s way by Hamas. Very much to the contrary. But given that the world has historically denied the Jews a place in the hierarchy of nations, I must ask, in the words of Pirqei Avot, the 2nd century collection of rabbinic wisdom (1:14), “Im ein ani li, mi li?” If I am not for myself, then who will be for me?

My relationship with Israel spans my whole life. I am grateful every day that I live in a world in which the Jews have a place to call home, a haven, the doors of which will always be open to us. Our ancestors did not have this for nearly 2,000 years, and some of us in this room even remember that time. I will do everything that I can to maintain that; to protect the people of the State of Israel.

In the coming weeks and months, you are going to hear all sorts of language that will be very upsetting. You will hear constant reminders of the body count in Gaza, and the humanitarian crisis there. You will hear falsehoods dismissing Israel as an “apartheid” or “settler colonialist” state, of practicing “genocide” or “ethnic cleansing.” You will hear descriptions of Palestinian “resistance,” calling for the destruction of Israel with chants of “Free Palestine” and the ever-popular “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.” You will hear terrorists who were trained and instructed to do horrible, horrible things to innocent Jewish civilians glorified as “martyrs.”

These are not the words of people who seek peace; this is not language of treaties and democratic governments living side-by-side. This is rather the language of terror, of destruction, of denying Jewish people the right to be, as we sing in Hatiqvah, Israel’s national anthem, “Am ḥofshi be-artzeinu.” A free people in our land.

And yet these words and ideas, the language of terrorism, has saturated our public discourse, not just online, but in print and on air and in the hearts of college students and even faculty who have been misled to believe that they are supporting freedom fighters in Gaza.

I learned this week that the Brandeis University Student Union Senate initially failed to pass a resolution condemning Hamas and calling for the return of hostages. The student senator who introduced the resolution claimed that his aim was to support “Jewish, Israeli, Palestinian, and Muslim students,” and to promote “empathy, tolerance, and informed discussion.”

Nevertheless, on Sunday, the vote was 6 in favor of condemning Hamas, 10 against, and 5 abstentions. Four days later, after much outcry, a new attempt apparently passed.

At Brandeis University, founded by Jews, for Jews, my sister’s alma mater, students could not muster the courage to condemn Hamas.

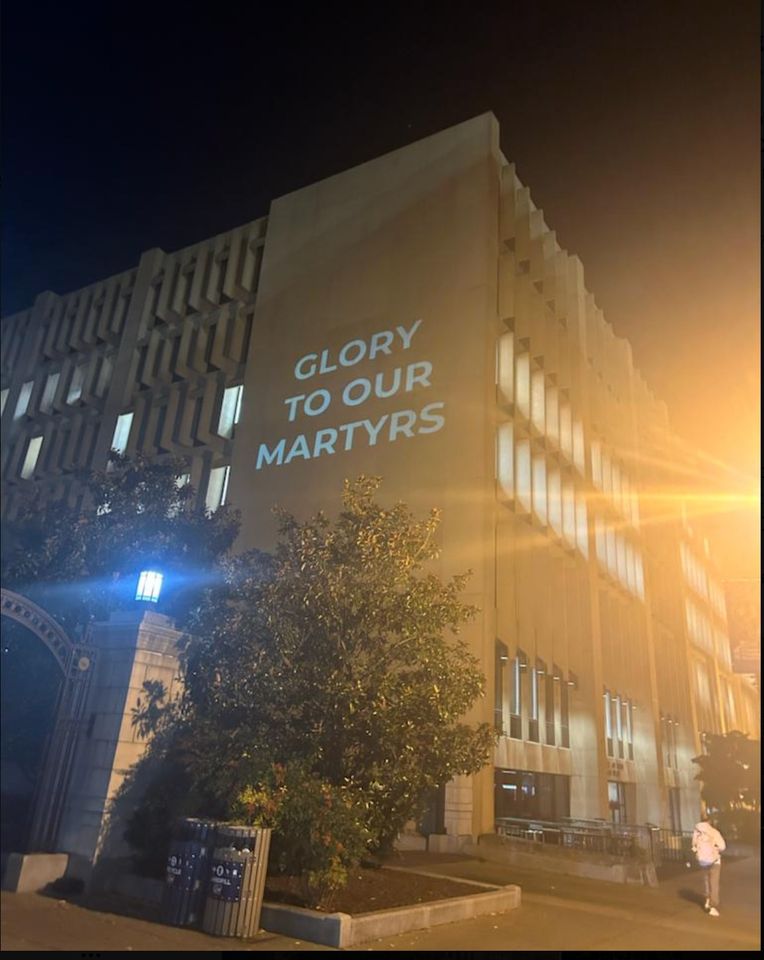

And that is a far cry from what has transpired at George Washington University, my brother’s alma mater, where events on campus have literally celebrated terrorism. The messages, “Glory To Our Martyrs,” “Divestment From Zionist Genocide Now,” and “Free Palestine From The River To The Sea” were projected onto the side of the Gelman Library on campus for two hours.

The newest wave in the ongoing gut-wrenching pain of the ordeal which we have faced since October 7 is not only the failure to condemn what is evil, but also the ideological assault on the very legitimacy of the Jewish state, the retelling of history which declares Israel to be the evil and glorifies terror. Perhaps we have lost the hearts and minds of the youth of America. Perhaps we should lament this, and be outraged. But outrage is not a strategy.

Rather, we have to take the long, reasoned view here. There are many obstacles to pursuing the two-state solution, but the primary irritant is Hamas, Islamic Jihad, Hizbullah, and of course the money and training which flows from Iran. This network of anti-Jewish terror does not want peace, nor would they be capable of creating a just, democratic state for the Palestinian people.

So what does this long path forward look like? I am not a policy expert, nor a military strategist, but I do have a fantasy:

Would this not be a great time for the international community, the West and the Arab world, to help Israel bring the hostages home, neutralize Hamas and help the Palestinians achieve a respectable solution? Israel cannot shoulder this burden alone.

On Thursday, I attended a unique event at Pitt hosted by our bar mitzvah’s mother Dr. Jennifer Murtazashvili, and her colleague Dr. Abdesalam Soudi. In the room were Jews and Muslims and people of other faiths, students and faculty. Such a gathering is particularly challenging in the current moment, when everybody is inflamed. But the point of the session was to find compassion for each other by telling stories, by sharing wisdom and music and yearnings.

It was a special moment in time, when people who might have found themselves in opposition to each other struggled to find compassion. It was also a reminder that the best way to change hearts and minds is by personal interaction, not through the intermediary of a screen.

If another generation of Israelis and Palestinians grow up without the realization of a two-state solution, empathy and compassion will be the greatest casualty.

Maimonides’ concept of concentric circles necessitates that we first demand the release of the captives. Im ein ani li mi li? If I am not for myself, then who will be for me?

And then we must stand up for Israel by making the case that the only way to make the democratic Palestinian state a reality – a compassionate reality – is by convincing our misguided friends and neighbors that Hamas is the enemy, not the standard-bearer of the Palestinian cause. Ukhshe-ani le’atzmi, mah ani? If I am only for myself, what am I?

Back in Parashat Lekh Lekha, when Hagar realizes that she is pregnant, she flees from her mistress Sarah, fearing Sarah’s mistreatment due to jealousy. And Hagar turns to God, to whom she refers as El Roi, meaning “God is my Shepherd.” God instructs her to return, and this moment in the Torah reminds us that God is pastor to all of God’s flock, particularly those who are in need of comfort and protection. God’s compassion for Hagar is palpable.

Judaism is a culture of life, not death. We do not rejoice at the death of our enemies. We remove wine from our cups at the Passover seder every year to remind ourselves of the Egyptian suffering created by our redemption from slavery. We continue to seek the peace between benei Sarah and benei Hagar, even as we are in pain, even as we mourn the dead and grieve for the hostages and lament the abhorrent cruelty of the attack on Israelis.

Adonai oz le’amo yiten; adonai yevarekh et amo vashalom. May God grant strength to God’s people; may God bless God’s people with peace.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Congregation Beth Shalom, Pittsburgh, PA, Shabbat morning, 10/28/2023.)