אֵיכָ֣ה יָשְׁבָ֣ה בָדָ֗ד הָעִיר֙ רַבָּ֣תִי עָ֔ם הָיְתָ֖ה כְּאַלְמָנָ֑ה רַבָּ֣תִי בַגּוֹיִ֗ם שָׂרָ֙תִי֙ בַּמְּדִינ֔וֹת הָיְתָ֖ה לָמַֽס׃

Alas! Lonely sits the city / Once great with people!

Eikhah / Lamentations 1:1

She that was great among nations / Is become like a widow;

The princess among states / Is become a thrall.

If you ever went to a Jewish summer camp, you may have encountered a long list of Jewish catastrophes that have taken place on Tish’ah BeAv, the ninth day of the month of Av. One item that often appears on this list is the signing of the edict of the Expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492. It sits alongside other such calamitous moments in Jewish history as the destruction of the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem (586 BCE and 70 CE, respectively) and the fall of the fortress of Betar in the Bar Kochba Rebellion in 135 CE.

Technically speaking, that is not historically accurate. The final edict of Expulsion was signed in the spring of 1492, not the summer. And, of course, it is worth noting that Spain was neither the first nor the last country from which the Jews were expelled.

Nonetheless, the Expulsion from Spain was tragic not only due to its scope and profound impact on the Jewish history of the last half-millennium, but also in particular because of the long and rich history of the Jews of the Iberian peninsula. Spain became, undeniably, the center of the Jewish world following the decline of the Iraqi Jewish community in the late first millennium.

In the 11th and 12th centuries, the Jews enjoyed a fruitful period of economic and intellectual development there. The ferment of Christian, Jewish, and Muslim philosophers and poets and scholars in that era led to a golden age for the Jews, spawning such brilliant contributors as Yehudah haLevi, Ramban (Nachmanides), Avraham ibn Ezra, Shemuel haNagid, Shelomoh Ibn Gevirol, and of course Rambam / Maimonides, the greatest figure of the Middle Ages.

While Judy and I were away from Pittsburgh during my sabbatical, we visited Toledo, which was for many centuries the spiritual center of Spain, for the Christians as well as the Jews. Under Christian rule from the late 11th century, Toledo became a center for translation between Arabic, Hebrew, and Castilian Spanish, and was therefore also the epicenter of cross-cultural intellectual development. There is a Jewish Quarter, which is identified on all the tourist maps, containing a few sites of Jewish interest, including two ancient synagogue buildings. According to our tour guide, there are only four known synagogue buildings from prior to 1492 which are still standing, this from the hundreds or maybe thousands which would have stood at the peak of Spain’s Jewish community.

Both synagogues at one time must have been grand buildings. The larger of the two, known as “El Tránsito,” was built in 1357 by Shemuel haLevi Abulafia, the treasurer to King Pedro I of Castile, also known as “Pedro the Cruel.” It has a lofty wooden ceiling and many decorative frescos and Hebrew inscriptions, including a dedication to King Pedro (who is referred to in large Hebrew letters as המלך דון פדרו / Hamelekh Don Pedro).

The smaller, older synagogue, known as “La Sinagoga de Santa María la Blanca,” dates to the late 12th century, and while it contains some lovely Moorish architectural features, virtually nothing can be seen of its original design.

Following the Expulsion, both buildings were repurposed as churches, which is why they are referred to by Christian names. “El Tránsito” is short for “El Tránsito de la Virgen María,” the “Dormition of the Virgin Mary.”

Judy and I paid a few Euros to visit these ancient buildings, which, despite their state, seem to ooze with history. El Tránsito features not only Hebrew inscriptions, but Arabic as well, as if to suggest that interfaith relations in the 14th century were hunky-dory.

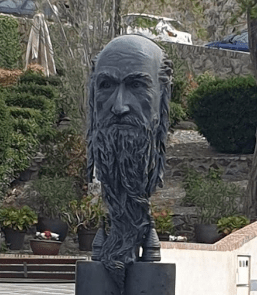

There is today no Jewish community to speak of in Toledo. For the nearest minyan, you have to drive an hour or so to get to Madrid. Shemuel haLevi Abulafia, who built that grand synagogue dedicated to Pedro the Cruel, was tortured to death by his employer a few years after it was built. His adjacent house now holds the El Greco museum and its collection of 16th-century Christian paintings. The main street through the center of the neighborhood is called “Calle de los Reyes Católicos,” the street of the Catholic Kings, and a contemporary sculpture of the 12 Christian apostles stands in a central square opposite an unflattering bust of Shemuel haLevi Abulafia, who is seemingly scowling at the apostles for not joining him for minyan.

In retrospect, the scene was really quite depressing. The so-called Jewish Quarter, where there are shops selling stylish menorahs and mezuzot and you can see artistic graffiti tags of חי (hai / life) and ספרד (Sefarad / Spain) all over the place, is no more Jewish than Utah’s Zion National Park. It is there for tourists, and nothing more. The majestic inscriptions on the walls of El Tránsito are merely museum pieces, not meant to inspire or bring the worshippers closer to God.

Alas! Lonely sits the city / Once great with people!

Traveling through Spain, we found Roman ruins in multiple places: aqueducts, city walls, bathhouses. It reminded us of Israel, except that in the latter, there are many much older pre-Roman sites as well. And the coast and countryside seemed in some sense like a mirror-image of Israel, reflecting across the Mediterranean: the rocky, arid landscape, the olive trees. I could not keep the words of Yehudah haLevi (ca. 1075 Toledo – 1141 Israel) from infiltrating my mind:

לִבִּי בְמִזְרָח וְאָנֹכִי בְּסוֹף מַעֲרָב / אֵיךְ אֶטְעֲמָה אֵת אֲשֶׁר אֹכַל וְאֵיךְ יֶעֱרָב

אֵיכָה אֲשַׁלֵּם נְדָרַי וֶאֱסָרַי, בְּעוֹד / צִיּוֹן בְּחֶבֶל אֱדוֹם וַאֲנִי בְּכֶבֶל עֲרָב

יֵקַל בְּעֵינַי עֲזֹב כָּל טוּב סְפָרַד, כְּמוֹ / יֵקַר בְּעֵינַי רְאוֹת עַפְרוֹת דְּבִיר נֶחֱרָב

My heart is in the East, and I in the uttermost West–

How can I find savor in food? How shall it be sweet to me?

How shall I render my vows and my bonds, while yet

Zion lies beneath the fetter of Edom, and I in Arab chains?

An easy thing would it seem to me to leave all the good things of Spain

Seeing how precious in mine eyes to behold the dust of the desolate sanctuary.

At the end of his life, Yehudah haLevi left Spain to travel to Israel. The apocryphal story is that upon reaching Jerusalem, he knelt down to kiss the ground, and was immediately trampled to death by an Arab horseman.

And yet, the irony is that Toledo today is effectively Judenrein, free of Jews, and Jerusalem is a thriving city filled with Jews, Christians, and Muslims. No, they do not always get along, but any imagined interfaith utopia in 11th century Spain was almost certainly equally fraught. I think Yehudah haLevi would have been pleased with the reality on the ground in Yerushalyim shel Matah, the Earthly Jerusalem, if not the politics found therein.

Perhaps the reality on the ground in today’s Toledo is roughly analogous to how Yehudah haLevi encountered Jerusalem when he made his journey across the Mediterranean; while Jerusalem had Jewish residents in the 12th century, it was at the time hardly an intellectual center for world Jewry; for Jews, it was largely a ruin, a place from which history had moved on.

One of the lessons of Shabbat Ḥazon, the “Shabbat of Vision” which always precedes Tish’ah beAv, is that true vision of the past, present, and future acknowledges that life comes with high points and low points. Freedom, democracy, self-determination: these represent high points in Jewish, and human, existence. Exile, dispersion, Inquisition, genocide are the low points. Our Jewish story includes all of these, and we should never feel so comfortable and high on ourselves as to forget the low points. That’s what Tish’ah beAv is for. That is why we have one day of the Jewish year set aside to commemorate our suffering. Life is not all sangría and roses.

We began the book of Devarim / Deuteronomy this week, and right up front Moshe reminds the Jews of their journey from slavery in Egypt through the wilderness. Our people have been on the move ever since.

What gives me hope, and what our people have cleaved to throughout our history is that as we have traveled from place to place, whether compelled to by sword or economics or persecution, we have continued to build and rebuild. Toledo was one stop along the Jewish journey; so too Baghdad, Warsaw, and New York. But I would pick Jerusalem over any of them. Yehudah haLevi’s yearnings rang in my ears driving through the Spanish countryside, passing castles and windmills and shopping malls, reminding me how fortunate we are to live in a time when my heart and my body can both be in the East, rather than the uttermost West.

Eikhah / the book of Lamentations concludes with a verse we know well. We sing it with gusto every time we put the Torah away:

הֲשִׁיבֵ֨נוּ ה’ אֵלֶ֙יךָ֙ וְֽנָשׁ֔וּבָה חַדֵּ֥שׁ יָמֵ֖ינוּ כְּקֶֽדֶם׃

Hashiveinu Adonai eilekha, venashuvah; hadesh yameinu keqedem.

Return us to you, Adonai, and we shall return; renew our days as of old.

Eikhah / Lamentations 5:21

The hopeful note after destruction is that we always have a chance to return, to rebuild. May that always be our vision for the future.

~

Rabbi Seth Adelson

(Originally delivered at Congregation Beth Shalom, Pittsburgh, PA, Shabbat morning, 7/22/2023.)